Difference between revisions of "Counterculture Through The Ages"

From Londonhua WIKI

Ekmceachern (talk | contribs) |

Ekmceachern (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

===Civil Rights Movement in the United States=== | ===Civil Rights Movement in the United States=== | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| − | ===Hippie Movement | + | ===Hippie Movement=== |

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

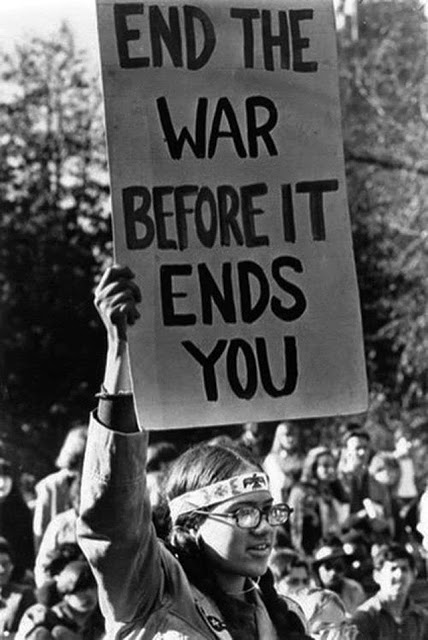

===Antiwar Movement=== | ===Antiwar Movement=== | ||

As the Vietnam war progressed, opposition to the war of the general public in America grew substantially. Both mass demonstrations organized by national groups and more local protests were important to the movements efforts<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. Groups like the American Friends Service Committee, the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, and the Women Strike for Peace were some of the main political groups involved in the movement<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. Many protestors believed that the Vietnam War took too many resources from other more important foreign interests and relations and used methods like peaceful protest to try to get the government to negotiate a settlement with Vietnam instead of continuing the war<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. The antiwar movement was made up of many different political groups. Radicals of this movement often used civil disobedience to protest many government actions of the U.S. and believed that electoral politics were unproductive. Pacifists that were part of this movement questioned the U.S. Cold War Policy. A small part of the antiwar movement was made up of Leftists. Leftists favored peaceful demonstrations to express their demands of the immediate removal of the U.S. from Vietnam<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. There was a lot of distrust among these three groups, making the antiwar movement very complicated<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. | As the Vietnam war progressed, opposition to the war of the general public in America grew substantially. Both mass demonstrations organized by national groups and more local protests were important to the movements efforts<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. Groups like the American Friends Service Committee, the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, and the Women Strike for Peace were some of the main political groups involved in the movement<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. Many protestors believed that the Vietnam War took too many resources from other more important foreign interests and relations and used methods like peaceful protest to try to get the government to negotiate a settlement with Vietnam instead of continuing the war<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. The antiwar movement was made up of many different political groups. Radicals of this movement often used civil disobedience to protest many government actions of the U.S. and believed that electoral politics were unproductive. Pacifists that were part of this movement questioned the U.S. Cold War Policy. A small part of the antiwar movement was made up of Leftists. Leftists favored peaceful demonstrations to express their demands of the immediate removal of the U.S. from Vietnam<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. There was a lot of distrust among these three groups, making the antiwar movement very complicated<ref>Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716</ref>. | ||

Revision as of 12:54, 13 June 2017

Contents

The History of Counterculture

Counterculture of the 1960s |

Abstract

This project aims to give a complete and extensive understanding of what counterculture is through the use of examples found it history. Also, it attempts to identify the counterculture of today. When people think of counterculture most of the time hippies and the 1960s will pop into their head, but time periods like the Enlightenment are also considered counterculture by its definition. I hope that after reading this project people will understand the complexity and quantity of countercultures throughout history. At WPI I have taken 2 History courses and 1 Philosophy course: HI 1332, HI 2332, and PY1731.

Introduction

I suggest you save this section for last. Describe the essence of this project. Cover what the project is and who cares in the first two sentences. Then cover what others have done like it, how your project is different. Discuss the extent to which your strategy for completing this project was new to you, or an extension of previous HUA experiences.

As you continue to think about your project milestones, reread the "Goals" narrative on defining project milestones from the HU2900 syllabus. Remember: the idea is to have equip your milestone with a really solid background and then some sort of "thing that you do". You'll need to add in some narrative to describe why you did the "thing that you did", which you'd probably want to do anyway. You can make it easy for your advisors to give you a high grade by ensuring that your project milestone work reflects careful, considerate, and comprehensive thought and effort in terms of your background review, and insightful, cumulative, and methodical approaches toward the creative components of your project milestone deliverables.

Section 1: Background

What is Counterculture?

A counterculture "rejects or challenges mainstream culture or particular elements of it" [1]. Most modern countercultural actions aim to show opposition, disagreement, or rebellion towards the current culture in place. Counterculture is often displayed through protesting against a particular issue, rebelling against an established way of doing things, trying to overcome oppression, and even creating a new culture when the one in place becomes dissatisfying[2]. Methods used to express countercultural points of view are meant to promote action and provoke changes among people. Often the unacceptability of counterculture is eventually taken as a normality by the general population and considered mainstream culture. This also makes it very difficult to identify a counterculture until a few years after it has originated. In the sections below I have included a few of the modern methods people use to express their countercultural point of view.

Methods

Demonstration

Demonstation is used as a way for people to come together to physically protest against a particular situation that they do not agree with[3]. Demonstrations can sometimes turn into violent riots, but in general they are one of the more peaceful forms of taking direct action against something. Peace protests have emerged to oppose the threat of war and even the development of dangerous technologies such as nuclear technology[4].

Civil Disobedience

Historically, the people participating in peace movements have been split on the decision whether to take more radical approaches of protest, like civil disobedience, or demonstration. Civil disobedience, like demonstration, is a form of direct action, but it differs from demonstration. This is because laws are broken in order to force an issue onto a political stage[5]. People that agree with civil disobedience argue that small crimes, like the disruption of streets, are justified because they are protesting a much large crime or issue, like war or environmental damages. However, in the eyes of authorities, the breaking of a law is never okay and participants of civil disobedience are often treated as trespassers.

In England, the philosopher Bertrand Russell was an advocate for civil disobedience and participated in sit-ins as a founder of the Committee of 100[6]. A sit in uses disruptions to attract attention to the cause that is being protested against. During a sit in protestors will sit in an area and refuse to move until their wants are met or they are removed by the authorities[7]. This method of protest was first used by Mahatma Gandhi and later adopted by others like Martin Luther King Jr. during the Civil Rights Movement.

Civil disobedience was also used by some of Bertrand Russell's Committee of 100 in the 1960s to find out and expose secret government information. Calling themselves the Spies for Peace, they supported people breaking into military bases and finding classified military information.

Living Demonstration

An example of living demonstration is squatting. This is where a person occupies an empty property without the owners permission or knowledge. To demonstrators, this method is both practical and symbolic because it gives a place for homeless people to live and also raises awareness to the issue of homelessness. The issue of homelessness in London has been controversial and taken seriously for a very long time. The development of the squatters movement, in the 1960s, relied on press coverage to get its message across, as do many living demonstration movements[8].

Disruption

Motivation for disruption often involves opposition to mainstream political processes and consumer culture. In the 1990s, disruption developed certain specific characteristics like opposition to the car and its destructive qualities, and a focus on civil freedom and democratic rights[9].

During the 1990s English protesters took preventative measures such as camping on construction sites of new roads to stop them from being built. Dedicated protestors even began moving from one protest site/community to another and they did not have a permanent home[10]. The people participating in this movement learned a lot from the squatters movement about how to get the attention of the media and how to avoid arrest. They eventually produced their own websites and other press about how to avoid arrest in a protest situation.

Underground Press

Underground Press in the UK began in October of 1966, when the first edition of the International Times was published. An article from the British Library writes, "The Underground Press didn't say what you thought, but it did somehow express what you felt" [11]. These publications aimed to express the growing counterculture of the 1960s in the UK where reporters wrote about changing attitudes of young people with a very "radical" voice. The underground press was given its name because it did not accept current, dominant cultural beliefs and when mainstream news carriers refused to sell the International Times, the writers and producers found young people to sell it to on the streets. Many of the underground papers were subject to police raids and were charged with obscenity and trying to corrupt public morals[12]. Even the layouts of the papers were hard to read and represented counterculture in a bold way.

Do it Yourself

"Do it Yourself" counterculture is all about stopping the consumption of the culture that was made for you and making your own culture. It is also a way to reject normal and accept ways of expressing oneself and developnew methods for self-expression [13].

Fanzines, also known as "zines", became a popular form of expressing counterculture before websites became a medium of communication. The reason they became so popular is that they are not dependent on any kind of publisher, are not motivated by profit, and are not filtered through anything. They are not as regulated and monitored as many other similar digital mediums, making them attractive to people looking for a place to freely express themselves [14]. Zines became so popular because they can be completely controlled by the person who created them. This helps to prevent misinterpretation, a problem that many countercultures have faces when dealing with mainstream media and press. Today, zines are not used much at all and the ones that are may never actually reach an audience.

Examples of Counterculture in History

The above methods of expressing countercultural points of view are mainly from the mid to late 20th century, but counterculture can be identified for far longer than this throughout history. Both the Enlightenment and Romanticism are not only intellectual movements, but are also great examples of counterculture in history before the 20th century. Of course these two movements are dramatically different than more modern countercultural movements in their methods used to portray an idea, but they are still important to the history of counterculture.

The Enlightenment

One of the most significant intellectual movements, and example of counterculture, to date is the Enlightenment. Enlightenment thinkers, mostly white males, institutionalized many intellectual values leaving lasting impacts even on todays society. As a counterculture, the Enlightenment movement formalized rationalism and made liberty a social contract[15]. Prior to the Enlightenment, European countries were ruled by only a few aristocrats who believed they had the power to do what they wanted with the world, which according to them was given to them by God. The Enlightenment went directly against these ideas and within 100 years, people of power were allowing others to discuss and spread whatever new ideas they wanted to[16].

The Enlightenment brought many new philosophical viewpoints including those of René Descartes, who proposed that reason could help people to understand the physical world. This kind of idea was revolutionary for the time and completely unlike previous medieval ideas[17]. Another philosopher, John Locke, went directly against the absolute monarchies of the time and stated that a government based on consent and majority ruling was the best way to govern a civil society[18]. Most likely the most important intellectual from the enlightenment was Francis Bacon, who is credited with the creation of the philosophy of modern science and technology. His ideas were completely opposite of medieval points of view, which stated that God, angels, and Satan are constantly interfering in the real world[19]. Also according to medieval ideas, there is no way to change the world to increase human happiness because it is not possible to change God's plan[20]. Bacon completely disagreed with this concept and argued that the way to true knowledge is to study the complexities of nature and the natural world.

In general, the freethinking of the enlightenment makes it a counterculture to the long medieval ages that came before it. Enlightenment thinkers publicly emphasized their opposition to religious philosophies of the past through their writings and statements of their new ideas. Eventually, like most countercultures, the ideas of Enlightenment thinkers became accepted among the majority of society.

Romanticism

Shortly after the beginning of the French Revolution, the Romanticism movement among intellectuals from both Europe and America took off, as a counterculture against the Enlightenment[21]. The Enlightenment challenged medieval kings, the church, class structure, and many other aspects of the previous society while romantics were extremely opposed to modern rationalism, which was a main product of the enlightenment. Romantic thinkers are often reffered to as being "anti-bourgeois'[22] and holding too tightly onto ancient ways of society. The Romantics of the first half of the 19th century completely rejected liberalism which has been puzzling to historians in the past. Liberalism and Democracy were denounced by some as being "herd-animalization" and a "form of decline in organizing power"[23].

The Romantic Period was a time of serious changes, where violent revolutions were taking place in both Europe and America. Poets like William Blake and William Wordsworth felt that they were "chosen" to help people through this changing and confusing time[24]. At the beginning of the Romantic period, Romantic poets in general were supporters of the French Revolution but changed their minds as the Reign of Terror came into reality. Romantic poets emphasized the idea that the imagination could help people overcome their troubles and Percy Bysshe Shelley even declared that poets "are the unacknowledged legislators of the world"[25]. Contrary to the Enlightenment, Romantic work was deeply rooted in the individual rather than focusing on society as a whole, and Romantics praised youth and innocence as being authoritative rather than those with age and experience. Romantics also believed that children held a special place in the world because of their innocent perspective[26]. In the writings of romantics they encouraged people to explore new places and made the world seem like it had unlimited opportunities for all.

Specific oppositions against the Enlightenment were shown through the introduction of the Gothic novel. One of the most famous Romantic novelists was Ann Radcliffe, who's work focused on struggling middle-class women who desired to see new places and inspiring landscapes[27]. Mary Shelley's famous work Frankenstein displays aspects of the Romantic movement, like the idea that scientific discoveries are driven by imagination, which is a direct contrast to that of the Enlightenment[28].

Art during the romantic period moved away from classical traditions and developed a new type of emotionalism that contrasted the ideas of "classical restraint"[29].

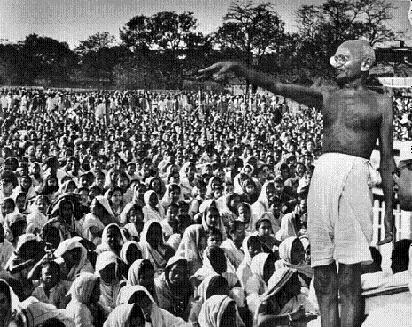

Indian Independence Movement

Prior 1917, when Mahatma Ghandi's leadership of the Indian National Congress(INC) began, movements against the British empire by the Indian people were not consistent and did not have much of an effect on the situation in the country. The Indian Independence movement took place from 1917 to 1947 with the INC at the head of the nonviolent protests[30]. Through Ghandi's leadership the INC went through many necessary changes, including alterations of their tactics for protest. Ghandi brought together both urban forces and the rural masses that were against the British occupation to challenge their colonial occupation. The INC adopted tactics of civil disobedience, nonviolent direct action, and noncooperation[31].

In 1919 the British Imperial government introduced a policy of dyarchy, which was the beginnings of local self-government. This policy gave administrative control to locally elected Indian officials[32]. Dyarchy also established an Imperial legislative government but with much less power than the local governments. In 1937 this policy was abolished, but India did not gain independence and remained under British control[33].

Ghandi reasoned with the INC that acts of civil disobedience would only be effective if they were carried out by large numbers of people, so the INC spread to have branches of the congress in each district of British India[34]. Civil disobedience was extremely popular with the Indian people and movements like the resistance campaign in 1917 and the anti-Rowlatt Bill satyagraha in 1919 were very successful[35]. The first mass national nonviolent movement was called the Noncooperation movement and took place from 1920-1922. The NCM was a series of local protests and as a result the 1920s was focused on forming relationships between urban nationalists in India and the smaller rural communities[36]. These newly formed connections improved rural participation in mass protest and civil disobedience in the 1930s. The most amazing movement made by the INC was the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) from 1930-1934. This movement began with the salt March, which was a 240 mile walk where Ghandi was arrested for public display of salt making[37]. His arrest launched massive acts of Civil Disobedience and within the first year of the CDM over 60,000 people had been arrested[38].

By 1934 the CDM ended due to an increase in repression by the Government of India. The use of nonviolence during the CDM brought many local successes and showed the immense power of the opposition but noncooperation tactics did not directly pressure the British to leave India. Acts of Civil Disobedience led by Ghandi and the INC, left the INC in a good position to negotiate with the British empire[39].

1960s counterculture

The rest of the background for this project will be focused on the complex counterculture of the 1960s. Many different countercultural movements emerged in the 1960s, and are very much related to each other, but they all fall under different categories of counterculture. Some were more political, while others are purely cultural, and some were a mix of both political and cultural motivations. Distinguishing between these differences is extremely important in helping to identify what todays countercultures are.

Civil Rights Movement in the United States

Hippie Movement

Antiwar Movement

As the Vietnam war progressed, opposition to the war of the general public in America grew substantially. Both mass demonstrations organized by national groups and more local protests were important to the movements efforts[40]. Groups like the American Friends Service Committee, the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, and the Women Strike for Peace were some of the main political groups involved in the movement[41]. Many protestors believed that the Vietnam War took too many resources from other more important foreign interests and relations and used methods like peaceful protest to try to get the government to negotiate a settlement with Vietnam instead of continuing the war[42]. The antiwar movement was made up of many different political groups. Radicals of this movement often used civil disobedience to protest many government actions of the U.S. and believed that electoral politics were unproductive. Pacifists that were part of this movement questioned the U.S. Cold War Policy. A small part of the antiwar movement was made up of Leftists. Leftists favored peaceful demonstrations to express their demands of the immediate removal of the U.S. from Vietnam[43]. There was a lot of distrust among these three groups, making the antiwar movement very complicated[44].

The antiwar movement started as a series of "teach-ins" on college campuses and the University of Michigan attracted a lot of attention when three thousand people attended a series of lectures on the Vietnam War in 1965[45]. Antiwar movements on college campuses began to become intertwined with civil rights issues and other social issues of the times. The movement in 1965 only represented a small part of the American populations beliefs but it attracted a lot of attention due to the media coverage of mass demonstrations[46]. Activists of this movement were often of the middle class and very well educated and the crowds of the mass demonstrations were made up of many college students.The military draft also contributed to the antiwar movement and many people resisted the draft legally and illegally[47].

The antiwar movement gained a negative image among moderate people of the country due to the Government's attacks on the movement. The presence of countercultural clothing and styles among many people of the movement also made many moderates more than hesitant to join the movement[48]. Government and administrative officials also accused the antiwar movement as being controlled by communists, also hindering its popularity[49].

The expansion of the war into Cambodia in 1970 also caused the movement to explode with protests in reaction to the controversial decision[50]. Protests on college campuses became dangerous and 5 people were even killed on the Kent State University campus after National Guardsman fired into the crowd[51]. Polls at the time showed that most Americans actually supported the decision to move into Cambodia, but the increase in protest created a predicament for the government[52]. Protests continued until the official conclusion of the war and eventually the public accepted the purpose of the movement even though in rejected the people that participated in the movement.

Gay Liberation Front

One very important movement that began in the 1960s was the Gay Liberation movement. This movement was led by young people who worked with organizations like the Mattachine Society, the Society for Individual Rights, and the Council on Religion and the Homosexual[53]. Activists of this time period were working to abolish the idea that homosexuality was a sickness, which was a normal and accepted idea of the time[54]. These groups were aiming to help gay men and women of the time by providing social services, fighting discrimination, and developing a new, positive gay culture in American cities. This was a completely revolutionary idea for the time, and the 1960s made many advances that helped the movement grow in the future. After a riot in a bar in Greenwich Village in New York City in 1969, known as the Stonewall riot, The Gay Liberation Front was formed and in only 4 years there was over 800 gay organizations[55]. The political activism of the time was marked by this expanse in support for the gay liberation movement.

The Gay Liberation movement continued into the 1970s and in 1971 the Gay Liberation Front published their manifesto in London. The purpose of this manifesto was to explain to people for homosexuals were oppressed and what the aims of their movement were. The introduction of the manifesto says, "Homosexuals, who have been oppressed by physical violence and by ideological and psychological attacks at every level of social interaction, are at last becoming angry" [56]. Homosexual people of the 1960s and 1970s felt that they needed to fight against their oppression and claim their rights as other groups have in the past. The document also explains the many ways that gay people are oppressed like through school, the media, the law, and even physical violence among many other things [57]. The manifesto explains why they are oppressed, stating "There are only these two stereotyped roles into which everyone is supposed to fit, and most people-including gay people too-are apt to be alarmed when they hear these stereotypes or gender roles attacked" [58]. According to the manifesto gay people were oppressed in the 1960s because they did not fit into gender roles of the family dynamic. The rest of the manifesto focuses on what the movement will do to change their situation and the new life that gay people will have once discrimination against them no longer has a place in society.

This countercultural movement is both a political and cultural one. The Gay Liberation movement sought to make homosexuals accepted in general society but also to give them the same rights as straight people through the establishment of laws of equality.

Section 2: Deliverable

Today's Countercultures

Conclusion

In this section, provide a summary or recap of your work, as well as potential areas of further inquiry (for yourself, future students, or other researchers).

References

- Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- Murphy, D. D. (n.d.). Romanticism and Counterculture The Rise of an Alienated Intellectual Subculture . Retrieved June 07, 2017, from http://dwightmurphey-collectedwritings.info/M4-Ch3.htm

- Forward, S. (2014, February 18). The Romantics. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-romantics

- T. (n.d.). Romanticism – Art Term. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/r/romanticism

- Goffman, K., & Joy, D. (2006). Counterculture through the ages: from Abraham to acid house. New York: Villard.

- Hall, S. (2008). Protest Movements in the 1970s: The Long 1960s. Journal of Contemporary History, 43(4), 655-672. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/40543228

- Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- Gay Liberation Front: Manifesto. (n.d.). Retrieved June 12, 2017, from http://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/pwh/glf-london.asp

- Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Counter Culture. (2006, September 22). Retrieved June 06, 2017, from http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/counterculture/counterintro.html

- ↑ Goffman, K., & Joy, D. (2006). Counterculture through the ages: from Abraham to acid house. New York: Villard.

- ↑ Goffman, K., & Joy, D. (2006). Counterculture through the ages: from Abraham to acid house. New York: Villard.

- ↑ Goffman, K., & Joy, D. (2006). Counterculture through the ages: from Abraham to acid house. New York: Villard.

- ↑ Goffman, K., & Joy, D. (2006). Counterculture through the ages: from Abraham to acid house. New York: Villard.

- ↑ Goffman, K., & Joy, D. (2006). Counterculture through the ages: from Abraham to acid house. New York: Villard.

- ↑ Goffman, K., & Joy, D. (2006). Counterculture through the ages: from Abraham to acid house. New York: Villard.

- ↑ Murphy, D. D. (n.d.). Romanticism and Counterculture The Rise of an Alienated Intellectual Subculture . Retrieved June 07, 2017, from http://dwightmurphey-collectedwritings.info/M4-Ch3.htm

- ↑ Murphy, D. D. (n.d.). Romanticism and Counterculture The Rise of an Alienated Intellectual Subculture . Retrieved June 07, 2017, from http://dwightmurphey-collectedwritings.info/M4-Ch3.htm

- ↑ Murphy, D. D. (n.d.). Romanticism and Counterculture The Rise of an Alienated Intellectual Subculture . Retrieved June 07, 2017, from http://dwightmurphey-collectedwritings.info/M4-Ch3.htm

- ↑ Forward, S. (2014, February 18). The Romantics. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-romantics

- ↑ Forward, S. (2014, February 18). The Romantics. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-romantics

- ↑ Forward, S. (2014, February 18). The Romantics. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-romantics

- ↑ Forward, S. (2014, February 18). The Romantics. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-romantics

- ↑ Forward, S. (2014, February 18). The Romantics. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-romantics

- ↑ T. (n.d.). Romanticism – Art Term. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/r/romanticism

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Crist, J. T. (2013). Indian Independence Movement. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, M. (2004). The Vietnam Era Antiwar Movement. OAH Magazine of History, 18(5), 13-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/25163716

- ↑ Hall, S. (2008). Protest Movements in the 1970s: The Long 1960s. Journal of Contemporary History, 43(4), 655-672. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/40543228

- ↑ Hall, S. (2008). Protest Movements in the 1970s: The Long 1960s. Journal of Contemporary History, 43(4), 655-672. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/40543228

- ↑ Hall, S. (2008). Protest Movements in the 1970s: The Long 1960s. Journal of Contemporary History, 43(4), 655-672. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.wpi.edu/stable/40543228

- ↑ Gay Liberation Front: Manifesto. (n.d.). Retrieved June 12, 2017, from http://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/pwh/glf-london.asp

- ↑ Gay Liberation Front: Manifesto. (n.d.). Retrieved June 12, 2017, from http://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/pwh/glf-london.asp

- ↑ Gay Liberation Front: Manifesto. (n.d.). Retrieved June 12, 2017, from http://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/pwh/glf-london.asp