Difference between revisions of "Green Spaces in London"

From Londonhua WIKI

(→Section 1: Background) |

|||

| (55 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

|bodystyle = width:25em | |bodystyle = width:25em | ||

|image = [[File:image.jpg|x450px|alt=Milestone Image]] | |image = [[File:image.jpg|x450px|alt=Milestone Image]] | ||

| − | | | + | |data1 = Hampstead Heath, One of London's Oldest Public Green Spaces<ref>London, T. O. (2012, June 20). Hampstead Heath Swimming Ponds. Retrieved June 20, 2017, from https://www.timeout.com/london/outdoor/hampstead-heath-swimming-ponds</ref> |

}} | }} | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

=Abstract= | =Abstract= | ||

| − | + | This milestone focused on providing a retrospective analysis of green spaces in London. The most recent course I had taken before being a part of London was Topics in American Social History, which focused on green spaces and their development in Worcester, MA. Inspired by this experience, this project presents London's complex history with greens spaces, with the deliverable component consisting of a informational pamphlet. Coming from a familiarity with the green space landscape of the small city of Worcester, London's long relationship with public green spaces presented a challenge to create a means to present such a rich background. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

=Introduction= | =Introduction= | ||

| − | + | <br> | |

| + | This milestone covers | ||

Cover what the project is and who cares in the first two sentences.<br> | Cover what the project is and who cares in the first two sentences.<br> | ||

Cover what others have done like it, how your project is different. <br> | Cover what others have done like it, how your project is different. <br> | ||

| Line 28: | Line 26: | ||

=Section 1: Background= | =Section 1: Background= | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | The city of London boasts 'an astonishing sixty seven square miles of parks, commons, community gardens, garden squares, nature reserves and churchyards to be enjoyed'<ref>Billington, J., & Lousada, S. (2003). Introduction. In London's Parks and Gardens (p. ii). London: Frances Lincoln.</ref> such a diverse quantity of green spaces within an urban setting comes only as a result of of a long evolutionary process, beginning in the late eighteenth century. | + | The city of London boasts 'an astonishing sixty seven square miles of parks, commons, community gardens, garden squares, nature reserves and churchyards to be enjoyed'<ref>Billington, J., & Lousada, S. (2003). Introduction. In London's Parks and Gardens (p. ii). London: Frances Lincoln. pg. 1-2.</ref> such a diverse quantity of green spaces within an urban setting comes only as a result of of a long evolutionary process, beginning in the late eighteenth century. |

| − | <ref> | + | <ref>Reeder, D. (2006). The European city and green space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850-2000. Aldershot: Ashgate.,ch. 3. pg. 30.</ref> |

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

==Pre-Modern Development== | ==Pre-Modern Development== | ||

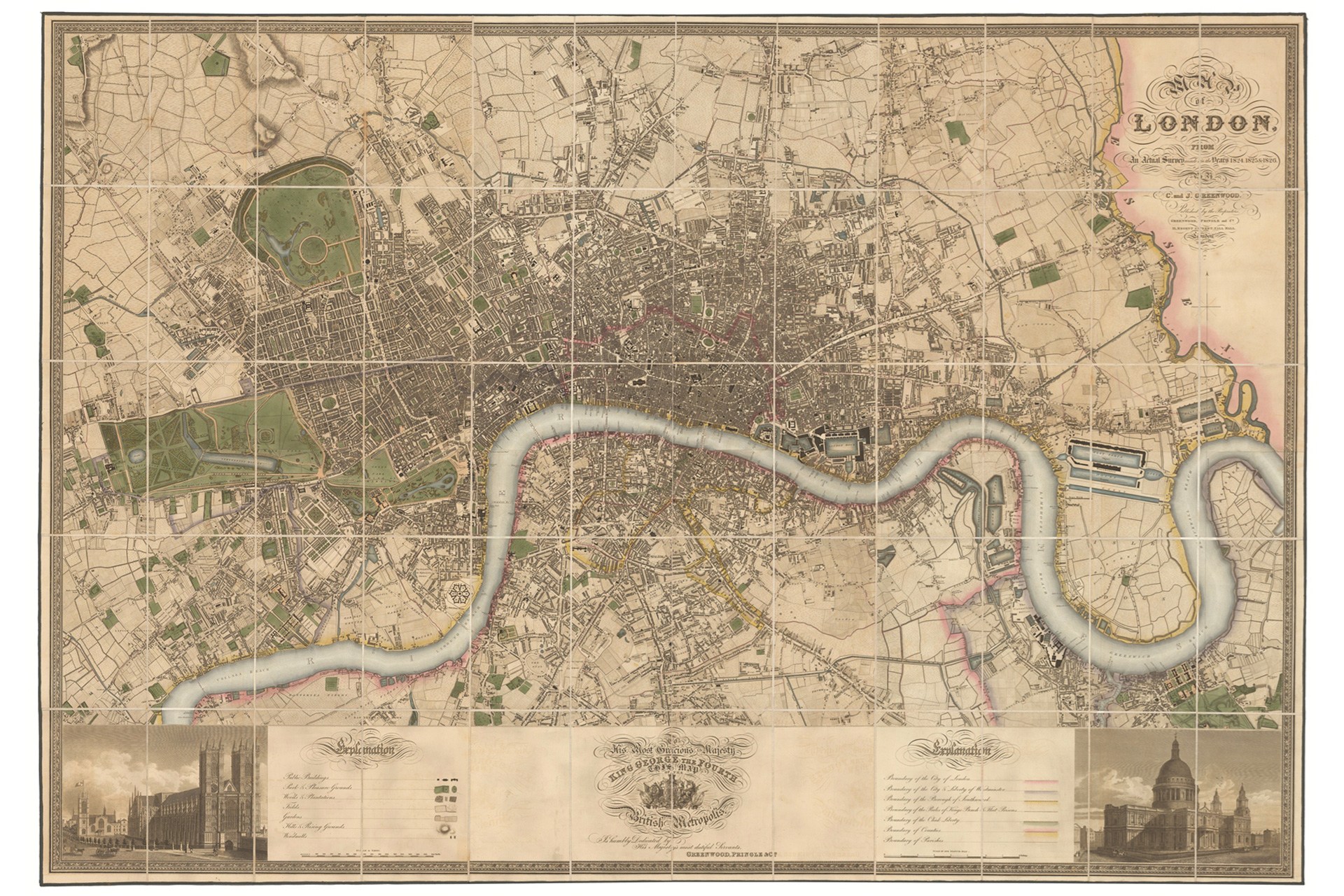

[[Image: Greenwood Map 1827.jpg|x320px|right|thumb|Greenwood's Map of 1827.<ref>Fowler, L. (2013, June 7). London in vintage maps. Retrieved June 19, 2017, from http://www.cntraveller.com/photos/photo-galleries/vintage-maps-of-london</ref>]] | [[Image: Greenwood Map 1827.jpg|x320px|right|thumb|Greenwood's Map of 1827.<ref>Fowler, L. (2013, June 7). London in vintage maps. Retrieved June 19, 2017, from http://www.cntraveller.com/photos/photo-galleries/vintage-maps-of-london</ref>]] | ||

| − | + | Like any aspect of history, nothing occurs in a vacuum. Most prestigious green spaces that would become public space derived from aristocratic and royal residences. Parks on the West End eventually became staples in London's Image as a capital city. Of these parks, Hyde Park would be the earliest one to successfully combine pleasures of the elite, including walking and riding, with more popular recreational use. In the late 1700s, population pressure on older central London began to change the character of a pre-existing green London as | |

| − | + | older commercialized pleasure gardens began to disappear alongside earlier forms of natural green space. Several London commons, part of manorial legacies, persevered through. | |

| − | Parks | + | The green spaces that survived this decline in public green space can be seen on Greenwood's map of 1827, clearly marked in green. at the turn of the nineteenth century, rights of public access had yet to be established in London, however commons such as Hampstead Heath and Epping Forest had become recreational areas simply by customary usage. |

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | Following this seeming decline, or at the very least stagnation, of green space, period of innovation took place. Through aristocratic estate developers, villa architects and landscape gardeners, new forms of landscaped open space took shape over the following years. Aristocratic estates would pioneer the convention of 'the square garden', a fairly self-explanitory title. While much of these innovative practices remained private within private estates, the early nineteenth century say a stronger emphasis on public access alongside green space development. In the 1830s, Kew Gardens and botanical and zoological gardens in Regent's Park were opened to the public. Regents Park's layout, planned by John Nash in 1818, successfully adapted the picturesque design features of the aristocratic country park to an urban setting. Nash's protégé, James Pennethorne, contributed largely to the shaping of the park's landscape, emphasizing an English style of landscaped urban park with ornamental water features. Two standout green spaces of this era were Victoria(1845) and Battersea Park (1860), which, as the largest and most costly, exemplified the concept of the people's park. | ||

| + | <ref>Reeder, D. (2006). The European city and green space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850-2000. Aldershot: Ashgate.,ch. 3. pg. 30-31.</ref> | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Green Spaces' Introduction to the Modern Era== | ||

| + | [[File: Temple Bar, Strand.png|thumb|left|Temple Bar, London Covered in Smog in 1844<ref>Smythe. (1844). Temple Bar, Strand [Photograph]. Metropolitan Prints Collection, Collage: The London Picture Archive, London.</ref>]] | ||

| + | The hundred years following the 1860s saw a significant expansion of green space in London. Through this, much of the ground work on which London built its diverse array of green spaces came into being. These years saw the regulation of commons and the formation of parks, communal gardens and smaller recreational areas across London's urban landscape. The number of commons acquired increased in the 1870s and small open spaces saw proliferation in the 1880 to 1890s. A steady progress of park creation dominated the 1880s to the 1930s. Over this period, metropolitan expansion and changing patterns of recreational activity in the years following World War I, green spaces saw a large diversification. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | Following the first World War, professional and political focus turned to examine to the future of London and quality of life of Londoners. Persistent atmospheric pollution proved a dominant issue pressing the city, emphasized by repeated episodes of city-wide smoke fogs. Subsequently, a call for exposing Londoners to more air and light came into action. At the same time, popular interest in outside play and keeping fit had grown in the inter-war years, which called for access to playing fields and recreational facilities. Works representative of a new generational awareness of the need for open space provisions with a planned approach to reconstruction of central London, with more effective control over land. A number of planners and environmental reformers held to a common belief in the possibility of raising the tone of society through recreating a sense of community and civic duty, a mentality evolved into London's so-called "Garden City movement." One of such advocates,Sybilla Gurney, described the movement as one that seeks, "to transform the modern congeries of persons into a real community - to make citizens as well as cities - and to restore the interaction of town and country". | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | < | + | London's long relationship with urban green spaces aptly defies simplicity. From individual activists to city officials to politicians to the actual landowners, the path by which London as a host of green spaces relied on all these constituents to come to a consensus of what London as a city should and ought to be. An incredible amount of interests were deeply involved in the social construction of London's green spaces: local residents, park and garden users, the staff of parks departments, school authorities, institutions, clubs, and societies, and a varitety of propery interests all had a part to play. This period undoubtedly saw a developing agreement over the value of open spaces, as well as illustrating that unfortunately there was no straightforward consensus but contained problematic elements like saving the London commons. Pressures like this only intensified in the aftermath of WWII. |

| − | + | <ref>Reeder, D. (2006). The European city and green space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850-2000. Aldershot: Ashgate.,ch. 3. pg. 31-67.</ref><br><br> | |

| − | + | ==Modern and Post-Modern Green Spaces== | |

| − | + | <br> | |

| − | + | Entering the late 20th century, 1939 to 2000 witnessed a raised concern over London's structure and governance. political and economic issues intersected with environmental issues as problems of open spaces and regional government, social inequality, economic revival, population distribution, and industrial and business location arose. Despite receiving scant priority immediately after WWII, open green spaces remained a strong pillar of social and civic importance to Londoners. public open green spaces were seen as a solution to urban turmoil, with areas being cleared for development of potential green spaces. At this time, green spaces became increasingly seen as a way to a means to contact with nature, improve social cohesion, and even enhance London's reputation as an international capital city.<br> | |

| − | + | Out of this, London, with unexpected growth in the later 20th century, paired with London's peripheral expansion and 1970s appetite for job creation, lead to a blurring of lines between London and the english countryside. Industrial and urban features and techniques took root across England, making the comparison between urban and rural began to evaporate. As a result, PMs went about adopting and providing for 'the more gregarious forms of outdoor recreation,' presenting a variety of solutions in the form of exploiting green spaces. Effort were made to promote defined areas like 'country parks' to contain visitors and tourists. Organized activities were provided for young people in national Park away from the metropolis of London. In 1968 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act focused on containing recreational demands from a increasingly affluent society. By these means, recreational green spaces became clearly distinct from open countryside. Through policy and debate, the 20th century ensured Green open spaces remained unique, however they were no longer primarily valued as a countermeasure to London's problems of crowding and pollution. With this, Open green spaces continued to strike the balance between public and private. | |

| − | + | <ref>Garside, P. (2006). The European city and green space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850-2000. Aldershot: Ashgate.,ch. 4. pg. 68-92</ref> | |

| − | <ref> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Contemporary Green Spaces== |

| − | + | The importance of green spaces in towns and cities has been recognized to varying degrees since the 19th century. The apparent value of green spaces in providing an escape from widespread urban air pollution serving as a major driver in creating new parks and green spaces. Over the last 20 years, a rise in interest has taken shape for quality and quantity of green space in urban areas. Three major factors have contributed to this trend: 1) concern about the decline in the quality of green spaces, due largely to low priority in the political agenda on national and local levels, 2) emphasis on the necessity for more intensive development in urban area, informed by "the hight-density 'compact city' " as the model for European cities and where green spaces fit into that, and 3)Improved evidence base supporting the benefits of urban green space, and environmental social and economic value to society. This upsurge reflected as an increase in research and professional activity in the environmental community. In the United Kingdom, a number of key documents produced in the last decade has led to government recognition of the vital importance of urban parks and green spaces as key components of urban environments. Specifically, the Urban Task Force Report and the Urban White Paper, DETR 2000, pointed to the significance of urban green space on the developing urban environment and urban city life. | |

| − | + | <ref>Swanwick, Carys, Nigel Dunnett, and Helen Woolley. "Nature, Role and Value of Green Space in Towns and Cities: An Overview." 29.2 (2003): 94-106. Web. 14 June 2017. pg. 92-105.</ref> | |

| − | + | <br><br> | |

| − | + | ==Hyde Park== | |

| − | + | Hyde park consisting of over 350 acres land stands as one of London's most famous royal park. While Hyde Park's land has likely been in use for millennia, the history of the land as a park dates back to Henry VII "acquiring" it from the monks of Westminster Abbey in 1536, as part of his establishment of the Church of England. Once under his authority, Henry VII and his court used the land as a hunting ground to the hunt for deer and similar game. Hyde Park would remain a private hunting ground until James I came to the throne and permitted limited access to non-royals. James I made the pivotal decision of establishing Hyde Park as a park for the people with his opening the land to the general public in 1637. Over the years following its establishment as a royal park, Hyde Park has changed in its appearance and well as its use by Londoners. In 1665, Londoners fled to camp on Hyde Park, in the hope of escaping the pervasive disease in the city. By end of the 17th century, Royalty called for adding artificially lighting along a path frequented by the new king, William III. Lit by 300 oil lamps, King's Road, more famously known as Rotten Row, became the first road in England to be lit at night. The next renovations came in the 1730s with Queen Caroline, wife of George II, pushing for extensive renovations carried out. Of these renovations, the most significant notable was the construction of Hyde Park's Serpentine, the parks massive human-made lake.<ref>History and Architecture. (2017). Retrieved June 20, 2017, from https://www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/hyde-park/about-hyde-park/history-and-architecture</ref> Following this, Hyde Park remained the same for almost 100 years until the 1820s when King George IV employed Decimus Burton to construct an entrance at Hyde Park Corner. Burton went on to replace the park's walls with railings and designed several new lodges and gates, as well. From then on, majority of how Hyde Park appears today is Decimus Burton left it back almost 200 years ago.<ref>Landscape History. (2017). Retrieved June 20, 2017, from https://www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/hyde-park/about-hyde-park/landscape-history</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The importance of green spaces in towns and cities has been recognized to varying degrees since the 19th century. The apparent value of green spaces in providing an escape from widespread urban air pollution serving as a major driver in creating new parks and green spaces. | ||

| − | Over the last 20 years, a rise in interest has taken shape for quality and quantity of green space in urban areas. Three major factors have contributed to this trend: 1) concern about the decline in the quality of green spaces, due largely to low priority in the political agenda on national and local levels, 2) emphasis on the necessity for more intensive development in urban area, informed by "the hight-density 'compact city' " as the model for European cities and where green spaces fit into that, and 3)Improved evidence base supporting the benefits of urban green space, and environmental social and economic value to society. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | upsurge reflected as increase in research and professional activity | ||

| − | In the | ||

| − | |||

| − | significance of urban green space on the developing urban environment and urban city life | ||

| − | <ref>Swanwick, Carys, Nigel Dunnett, and Helen Woolley. "Nature, Role and Value of Green Space in Towns and Cities: An Overview." 29.2 (2003): 94-106. Web. 14 June 2017.</ref> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

=Section 2: Deliverable= | =Section 2: Deliverable= | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | The following is a pdf of a short pamphlet detailing green spaces change in definition over the last 200 years of English history. | |

| − | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Pamphlet on Green Space in London== |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | [https://londonhuawiki.wpi.edu/images/d/de/How_London_Has_Kept_Green.pdf How London Has Kept Green] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

=Conclusion= | =Conclusion= | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | Green space represents a basic human necessity of remain in contact, on some level, with nature. Most American cities take a measured departure from maintaining modern green space as progress and innovation demand more space. London stands out as an example of a European high-density 'compact city' progressive not only it technology as well as public green spaces. London benefits from a long history with green spaces, allowing implementation green space in the evolving cityscape at such a level. | |

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

=References= | =References= | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| Line 128: | Line 82: | ||

=External Links= | =External Links= | ||

| − | + | [[http://users.bathspa.ac.uk/greenwood/imagemap.html users.bathspa.ac.uk]] - Website dedicated to an detailed breakdown analysis of Greenwood's Map of 1827<br> | |

| + | [[https://www.london.gov.uk/WHAT-WE-DO/environment/parks-green-spaces-and-biodiversity/green-spaces-map www.london.gov.uk]] - Map of London's currently operational green spaces around the city | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

=Image Gallery= | =Image Gallery= | ||

[[Category:History Projects]] | [[Category:History Projects]] | ||

[[Category:2017]] | [[Category:2017]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:09, 23 June 2017

Green Spaces in London

by Cole Fawcett

| |

| Hampstead Heath, One of London's Oldest Public Green Spaces[1] |

Contents

Abstract

This milestone focused on providing a retrospective analysis of green spaces in London. The most recent course I had taken before being a part of London was Topics in American Social History, which focused on green spaces and their development in Worcester, MA. Inspired by this experience, this project presents London's complex history with greens spaces, with the deliverable component consisting of a informational pamphlet. Coming from a familiarity with the green space landscape of the small city of Worcester, London's long relationship with public green spaces presented a challenge to create a means to present such a rich background.

Introduction

This milestone covers

Cover what the project is and who cares in the first two sentences.

Cover what others have done like it, how your project is different.

Discuss the extent to which your strategy for completing this project was new to you, or an extension of previous HUA experiences.

Add in some narrative to describe why you did the "thing that you did", which you'd probably want to do anyway.

Section 1: Background

The city of London boasts 'an astonishing sixty seven square miles of parks, commons, community gardens, garden squares, nature reserves and churchyards to be enjoyed'[2] such a diverse quantity of green spaces within an urban setting comes only as a result of of a long evolutionary process, beginning in the late eighteenth century.

[3]

Pre-Modern Development

Like any aspect of history, nothing occurs in a vacuum. Most prestigious green spaces that would become public space derived from aristocratic and royal residences. Parks on the West End eventually became staples in London's Image as a capital city. Of these parks, Hyde Park would be the earliest one to successfully combine pleasures of the elite, including walking and riding, with more popular recreational use. In the late 1700s, population pressure on older central London began to change the character of a pre-existing green London as

older commercialized pleasure gardens began to disappear alongside earlier forms of natural green space. Several London commons, part of manorial legacies, persevered through.

The green spaces that survived this decline in public green space can be seen on Greenwood's map of 1827, clearly marked in green. at the turn of the nineteenth century, rights of public access had yet to be established in London, however commons such as Hampstead Heath and Epping Forest had become recreational areas simply by customary usage.

Following this seeming decline, or at the very least stagnation, of green space, period of innovation took place. Through aristocratic estate developers, villa architects and landscape gardeners, new forms of landscaped open space took shape over the following years. Aristocratic estates would pioneer the convention of 'the square garden', a fairly self-explanitory title. While much of these innovative practices remained private within private estates, the early nineteenth century say a stronger emphasis on public access alongside green space development. In the 1830s, Kew Gardens and botanical and zoological gardens in Regent's Park were opened to the public. Regents Park's layout, planned by John Nash in 1818, successfully adapted the picturesque design features of the aristocratic country park to an urban setting. Nash's protégé, James Pennethorne, contributed largely to the shaping of the park's landscape, emphasizing an English style of landscaped urban park with ornamental water features. Two standout green spaces of this era were Victoria(1845) and Battersea Park (1860), which, as the largest and most costly, exemplified the concept of the people's park.

[5]

Green Spaces' Introduction to the Modern Era

The hundred years following the 1860s saw a significant expansion of green space in London. Through this, much of the ground work on which London built its diverse array of green spaces came into being. These years saw the regulation of commons and the formation of parks, communal gardens and smaller recreational areas across London's urban landscape. The number of commons acquired increased in the 1870s and small open spaces saw proliferation in the 1880 to 1890s. A steady progress of park creation dominated the 1880s to the 1930s. Over this period, metropolitan expansion and changing patterns of recreational activity in the years following World War I, green spaces saw a large diversification.

Following the first World War, professional and political focus turned to examine to the future of London and quality of life of Londoners. Persistent atmospheric pollution proved a dominant issue pressing the city, emphasized by repeated episodes of city-wide smoke fogs. Subsequently, a call for exposing Londoners to more air and light came into action. At the same time, popular interest in outside play and keeping fit had grown in the inter-war years, which called for access to playing fields and recreational facilities. Works representative of a new generational awareness of the need for open space provisions with a planned approach to reconstruction of central London, with more effective control over land. A number of planners and environmental reformers held to a common belief in the possibility of raising the tone of society through recreating a sense of community and civic duty, a mentality evolved into London's so-called "Garden City movement." One of such advocates,Sybilla Gurney, described the movement as one that seeks, "to transform the modern congeries of persons into a real community - to make citizens as well as cities - and to restore the interaction of town and country".

London's long relationship with urban green spaces aptly defies simplicity. From individual activists to city officials to politicians to the actual landowners, the path by which London as a host of green spaces relied on all these constituents to come to a consensus of what London as a city should and ought to be. An incredible amount of interests were deeply involved in the social construction of London's green spaces: local residents, park and garden users, the staff of parks departments, school authorities, institutions, clubs, and societies, and a varitety of propery interests all had a part to play. This period undoubtedly saw a developing agreement over the value of open spaces, as well as illustrating that unfortunately there was no straightforward consensus but contained problematic elements like saving the London commons. Pressures like this only intensified in the aftermath of WWII.

[7]

Modern and Post-Modern Green Spaces

Entering the late 20th century, 1939 to 2000 witnessed a raised concern over London's structure and governance. political and economic issues intersected with environmental issues as problems of open spaces and regional government, social inequality, economic revival, population distribution, and industrial and business location arose. Despite receiving scant priority immediately after WWII, open green spaces remained a strong pillar of social and civic importance to Londoners. public open green spaces were seen as a solution to urban turmoil, with areas being cleared for development of potential green spaces. At this time, green spaces became increasingly seen as a way to a means to contact with nature, improve social cohesion, and even enhance London's reputation as an international capital city.

Out of this, London, with unexpected growth in the later 20th century, paired with London's peripheral expansion and 1970s appetite for job creation, lead to a blurring of lines between London and the english countryside. Industrial and urban features and techniques took root across England, making the comparison between urban and rural began to evaporate. As a result, PMs went about adopting and providing for 'the more gregarious forms of outdoor recreation,' presenting a variety of solutions in the form of exploiting green spaces. Effort were made to promote defined areas like 'country parks' to contain visitors and tourists. Organized activities were provided for young people in national Park away from the metropolis of London. In 1968 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act focused on containing recreational demands from a increasingly affluent society. By these means, recreational green spaces became clearly distinct from open countryside. Through policy and debate, the 20th century ensured Green open spaces remained unique, however they were no longer primarily valued as a countermeasure to London's problems of crowding and pollution. With this, Open green spaces continued to strike the balance between public and private.

[8]

Contemporary Green Spaces

The importance of green spaces in towns and cities has been recognized to varying degrees since the 19th century. The apparent value of green spaces in providing an escape from widespread urban air pollution serving as a major driver in creating new parks and green spaces. Over the last 20 years, a rise in interest has taken shape for quality and quantity of green space in urban areas. Three major factors have contributed to this trend: 1) concern about the decline in the quality of green spaces, due largely to low priority in the political agenda on national and local levels, 2) emphasis on the necessity for more intensive development in urban area, informed by "the hight-density 'compact city' " as the model for European cities and where green spaces fit into that, and 3)Improved evidence base supporting the benefits of urban green space, and environmental social and economic value to society. This upsurge reflected as an increase in research and professional activity in the environmental community. In the United Kingdom, a number of key documents produced in the last decade has led to government recognition of the vital importance of urban parks and green spaces as key components of urban environments. Specifically, the Urban Task Force Report and the Urban White Paper, DETR 2000, pointed to the significance of urban green space on the developing urban environment and urban city life.

[9]

Hyde Park

Hyde park consisting of over 350 acres land stands as one of London's most famous royal park. While Hyde Park's land has likely been in use for millennia, the history of the land as a park dates back to Henry VII "acquiring" it from the monks of Westminster Abbey in 1536, as part of his establishment of the Church of England. Once under his authority, Henry VII and his court used the land as a hunting ground to the hunt for deer and similar game. Hyde Park would remain a private hunting ground until James I came to the throne and permitted limited access to non-royals. James I made the pivotal decision of establishing Hyde Park as a park for the people with his opening the land to the general public in 1637. Over the years following its establishment as a royal park, Hyde Park has changed in its appearance and well as its use by Londoners. In 1665, Londoners fled to camp on Hyde Park, in the hope of escaping the pervasive disease in the city. By end of the 17th century, Royalty called for adding artificially lighting along a path frequented by the new king, William III. Lit by 300 oil lamps, King's Road, more famously known as Rotten Row, became the first road in England to be lit at night. The next renovations came in the 1730s with Queen Caroline, wife of George II, pushing for extensive renovations carried out. Of these renovations, the most significant notable was the construction of Hyde Park's Serpentine, the parks massive human-made lake.[10] Following this, Hyde Park remained the same for almost 100 years until the 1820s when King George IV employed Decimus Burton to construct an entrance at Hyde Park Corner. Burton went on to replace the park's walls with railings and designed several new lodges and gates, as well. From then on, majority of how Hyde Park appears today is Decimus Burton left it back almost 200 years ago.[11]

Section 2: Deliverable

The following is a pdf of a short pamphlet detailing green spaces change in definition over the last 200 years of English history.

Pamphlet on Green Space in London

Conclusion

Green space represents a basic human necessity of remain in contact, on some level, with nature. Most American cities take a measured departure from maintaining modern green space as progress and innovation demand more space. London stands out as an example of a European high-density 'compact city' progressive not only it technology as well as public green spaces. London benefits from a long history with green spaces, allowing implementation green space in the evolving cityscape at such a level.

References

- ↑ London, T. O. (2012, June 20). Hampstead Heath Swimming Ponds. Retrieved June 20, 2017, from https://www.timeout.com/london/outdoor/hampstead-heath-swimming-ponds

- ↑ Billington, J., & Lousada, S. (2003). Introduction. In London's Parks and Gardens (p. ii). London: Frances Lincoln. pg. 1-2.

- ↑ Reeder, D. (2006). The European city and green space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850-2000. Aldershot: Ashgate.,ch. 3. pg. 30.

- ↑ Fowler, L. (2013, June 7). London in vintage maps. Retrieved June 19, 2017, from http://www.cntraveller.com/photos/photo-galleries/vintage-maps-of-london

- ↑ Reeder, D. (2006). The European city and green space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850-2000. Aldershot: Ashgate.,ch. 3. pg. 30-31.

- ↑ Smythe. (1844). Temple Bar, Strand [Photograph]. Metropolitan Prints Collection, Collage: The London Picture Archive, London.

- ↑ Reeder, D. (2006). The European city and green space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850-2000. Aldershot: Ashgate.,ch. 3. pg. 31-67.

- ↑ Garside, P. (2006). The European city and green space: London, Stockholm, Helsinki and St Petersburg, 1850-2000. Aldershot: Ashgate.,ch. 4. pg. 68-92

- ↑ Swanwick, Carys, Nigel Dunnett, and Helen Woolley. "Nature, Role and Value of Green Space in Towns and Cities: An Overview." 29.2 (2003): 94-106. Web. 14 June 2017. pg. 92-105.

- ↑ History and Architecture. (2017). Retrieved June 20, 2017, from https://www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/hyde-park/about-hyde-park/history-and-architecture

- ↑ Landscape History. (2017). Retrieved June 20, 2017, from https://www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/hyde-park/about-hyde-park/landscape-history

External Links

[users.bathspa.ac.uk] - Website dedicated to an detailed breakdown analysis of Greenwood's Map of 1827

[www.london.gov.uk] - Map of London's currently operational green spaces around the city