Milestone 1: Homelessness Through the Eyes of a Lens

From Londonhua WIKI

The Unknown Monet of London

Your Project Page Picture Caption |

Contents

Abstract

The paragraph should give a three to five sentence abstract about your entire London HUA experience including 1) a summary of the aims of your project, 2) your prior experience with humanities and arts courses and disciplines, and 3) your major takeaways from the experience. This can and should be very similar to the paragraph you use to summarize this milestone on your Profile Page. It should contain your main Objective, so be sure to clearly state a one-sentence statement that summarizes your main objective for this milestone such as "a comparison of the text of Medieval English choral music to that of the Baroque" or it may be a question such as "to what extent did religion influence Christopher Wren's sense of design?"

Introduction

I suggest you save this section for last. Describe the essence of this project. Cover what the project is and who cares in the first two sentences. Then cover what others have done like it, how your project is different. Discuss the extent to which your strategy for completing this project was new to you, or an extension of previous HUA experiences.

As you continue to think about your project milestones, reread the "Goals" narrative on defining project milestones from the HU2900 syllabus. Remember: the idea is to have equip your milestone with a really solid background and then some sort of "thing that you do". You'll need to add in some narrative to describe why you did the "thing that you did", which you'd probably want to do anyway. You can make it easy for your advisors to give you a high grade by ensuring that your project milestone work reflects careful, considerate, and comprehensive thought and effort in terms of your background review, and insightful, cumulative, and methodical approaches toward the creative components of your project milestone deliverables.

PLEASE NOTE: this milestone template has only a few sections as examples, but your actual milestone should have many relevant sections and subsections. Please start to block out and complete those sections asking yourself "who, what, when, where, and why".

Remember, as you move toward your creative deliverable, you're going to want/need a solid background that supports your case, so you want it to paint a clear and thorough picture of what's going on, so that you can easily dissect your creative component and say "This thing I did is rooted in this aspect of my background research".

Section 1: Background

Monet's Life

Oscar-Claude Monet was born in Paris in November 14, 1840 to Claude Adolphe Monet and Louise Justine Aubrée Monet. At the age of 5, Money and his family moved to Le Havre in Normandy where his father wanted him to go into the family business of ship-chandling and grocery business, but Money had other ideas. [1] He was striving to be an artist rather than a shop owner and his mother, being a singer, supported his career in art. On the first of April, 1851, Monet entered the Le Havre secondary school of the arts and began to fulfill his dream. Locals at the time knew him well as he would sell his charcoal caricatures for ten to twenty francs. He took his first drawing lessons from Jacques-François Ochard and met Eugène Boudin on the beaches of Normandy in 1856. This is when Boudin taught him how to use oil paints and the techniques involved in “en plein air” paintings. [2] His mother died on January 28th, 1857 and at the age of sixteen, Monet left school to live with his widowed and childless aunt, Marie-Jeanne Lecadre. It was then that Monet visited the Louvre and painted his first works of art. [3] After being drafted into the First Regiment of African Light Cavalry in Algeria in 1861, Monet contracted typhoid fever and went absent without leave. It was then that his aunt intervened to get him out of the army so long as Monet agreed to a complete one course in an art school. He was hesitant because of his disappointment in the traditional curriculum taught in art school and instead became a student of Charles Gleyre in 1862 in Paris. This was the moment the first true forms of Impressionism were created. Monet, along with Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille and Alfred Sisley shared their different approaches to art and experimented with the effects of light outdoors through rapid and seemingly random brush strokes in conjunction with broken color schemes. He took these techniques with him across Europe painting different landscapes, buildings and environments and took his first trip to London in 1870-1. [4]

Monet in London

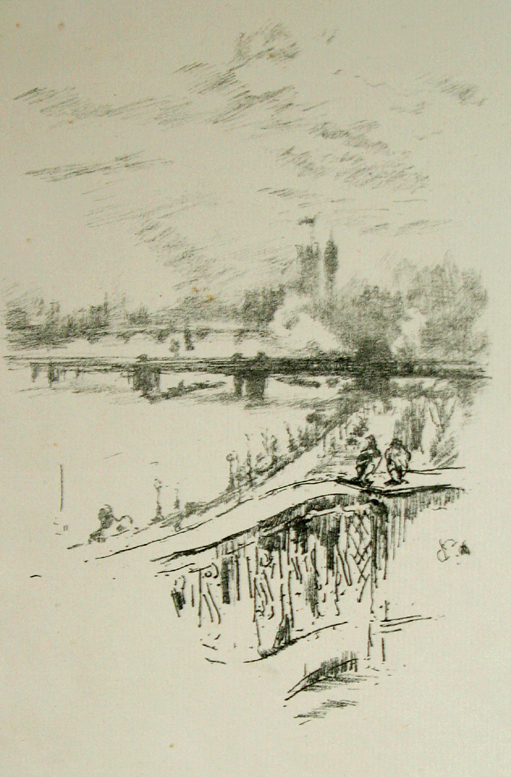

Lithograph of James McNeil Whistler |

The moment in arrive in London for the first time in 1870, Monet instantly fell in love with the atmospheric effects of the fog and the city itself. As soon as he left the city, he knew he wanted to come back and paint the city in all of its glory. Unfortunately, due to financial troubles at the time, he wasn't able to come back until 1899 when he could afford to stay at the Savoy Hotel, one of the world’s most luxurious hotels at the time. [5] It was there, on the sixth and fifth floor, that Monet created the London Series, a collection of 94 surviving oil paintings and many more that were never finished from 1899-1905. The current existing works consist of 19 paintings of Parliament, 41 of the Waterloo Bridge, and 34 of the Charing Cross Bridge. Monet would typically begin his day by painting the Waterloo and Charing Cross bridges and then paint the Houses of Parliament in the afternoon and evening. [6]

During the 18 month period surrounding Monet’s stay in London, he spent approximately 6 of those months in London painting the bridges. Monet chose the Savoy Hotel because of its remarkable view of all three landmarks displayed in his London Series and during his first stay from mid-September to the end of Octobeblr/early November in 1899, Monet lived in and painted from the sixth floor. When he returned from 9 February to 5 April in 1900, he noticed that the entirety of the sixth floor was being used for injured soldiers from the Boer War, as per Princess Louise’s request. [7] Because of this, Monet worked from a suite on the fifth floor during his second and again on his third stay from 25 January until the end of March in 1901. In the days of Monet, a suite would have consisted of a bedroom and a sitting room, and at the Savoy, a balcony. This hotel and the specific rooms were recommended to him by fellow artist and friend James McNeill Whistler.

It can be established that during his first stay at the Savoy, Monet most likely worked from a corner suite on the sixth floor that Whistler had previously occupied and recommended because of the view from the balcony.[8][9] Whistler’s room and viewing position can be discovered by analyzing his lithographs 'Savoy Pigeons’ and ‘Evening - Little Waterloo Bridge’. These lithographs were produced in 1896 while he stayed at the Savoy for several weeks comforting his wife, Trixie, who was terminally ill with cancer. In the corner of ‘Savoy Pigeons’, the birds can be seen on the corner balcony to the left. Exploring this image more closely, one can also see that there are no pillars in the image. This is because the pillars of the Savoy Hotel are only present to and including the fifth floor. It can then be concluded that Whistler was painting from the corner suite on the sixth floor of the hotel.

After being captivated by London and the London Fog, Monet set out to create the 'London Series', one of his most remarkable collections. In these urban paintings, people and their carriages, trains, and boats all gave way to the fog and the light peaking through. The natural light and mist provided a new way of demonstrating different moods and effects of the environment on architectural giants. From the Savoy Hotel, he could see the Waterloo Bridge on his left and the Charing Cross Bridge on his right and from St. Thomas hospital, he painted the magnificent House of Parliament series. It was not the light or the architecture that enthralled Monet so much, but the London Fog, which "dematerialized" the look of the River Thames, the bridges, and Parliament. Monet demonstrated this look and feel in his paintings by showing even less concern for detail than in his previous series of the Poplars. In the 'Houses of Parliament' series, soft and subtle tones of blues and pinks were used to signify the changing of light on the fog and on the city. [10] In 'Charing Cross Bridge, London', Monet used the fog to show how sunlight can be dispersed over a large area by using blues and pinks that slowly transformed backdrops of vivid yellow tones. Contrastingly, Monet reversed lights and darks in his 'Waterloo Bridge' series. This was done to create a new perspective on the city and its energy. By making the bridge a bright band of light and the people and their carriages small bursts of light, the energy of the city is intensified greatly. [11] As with all of his paintings, Monet put his genius imagination and memory to use to create a collection of masterpieces that will never be forgotten.

Towards the End

Claude Monet |

Monet began to develop cataracts after the death of his second wife, Alice, and his oldest son, Jean, in 1911 and 1914 respectively. [12] Before Jean's death, he had married Alice's daughter Blanche, Monet's favorite of the bunch. As Monet's sight began failing him and the cataracts worsened, Blanche moved to Giverny, France, where he lived, to take care of him. Monet's house in Giverny was the site of his famous garden and water lily pond. It was there that some of his most notable works were crafted into the masterpieces that we know today. It was also there that Monet paid homage to his younger son, Michel, his friend, Georges Clemenceau, and the other fallen French soldiers who had lost their lives in World War I through his paintings of the weeping willow trees. Due to Monet's cataracts, these paintings all had a reddish hue, a symptom common of many people who suffer from cataracts. It was not until 1923 that Monet had two operations done to remove his cataracts. After his operations, he began repainting older paintings with seemingly bluer water lilies than before. This may have been due to a possible lack in ability to see ultraviolet wavelengths of light that are normally excluded by the natural lens of the eye. [13] On the 5th of December, 1926, Monet fell victim to lung cancer and passed away at the age of 86. He is currently buried in a family grave in the Giverny church cemetery in France. [14] Only around fifty people came to the ceremony because Monet had always insisted that the occasion be small and simple. Today, tourists from all around the world can visit Monet's home and gardens which were given to French Academy of Fine Arts by his son, Michel, in 1966.

Section 2: Deliverable

In this section, provide your contribution, creative element, assessment, or observation with regard to your background research. This could be a new derivative work based on previous research, or some parallel to other events. In this section, describe the relationship between your background review and your deliverable; make the connection between the two clear.

Impressionism vs. Modern Photography

Impressionism Paragraph

Photography Paragraph

Similarities

Subsection 2

...and so on and so forth...

Gallery

Conclusion

In this section, provide a summary or recap of your work, as well as potential areas of further inquiry (for yourself, future students, or other researchers).

References

Add a references section; consult the Help page for details about inserting citations in this page.

Attribution of Work

For milestones completed collaboratively, add a section here detailing the division of labor and work completed as part of this milestone. All collaborators may link to this single milestone article instead of creating duplicate pages. This section is not necessary for milestones completed by a single individual.

External Links

If appropriate, add an external links section

Image Gallery

If appropriate, add an image gallery

Category tags

Don't forget to add category tags!!! Your Milestone Pages MUST contain one "Project" Category tags like this:

[[Category:Art Projects]]

[[Category:Music Projects]]

[[Category:Philosophy & Religion Projects]]

[[Category:Drama & Theater Projects]]

[[Category:Writing & Rhetoric Projects]]

[[Category:History Projects]]

[[Category:English Projects]]

...and NO OTHER TAGS except for the year the project was completed by you, like this:

[[Category:2017]]

See the Category Help page for assistance. Don't include irrelevant category tags in your Milestone page (like the Template category!)

Delete this entire "Category section" when editing this page--Categories don't need a heading.

- ↑ 'The New Encyclopaedia Britannica.' Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1974-01-01. p. 347. ISBN 9780852292907.

- ↑ 'Biography for Claude Monet Guggenheim Collection'. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ↑ Tinterow, Gary (1994). 'Origins of Impressionism'. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870997174.

- ↑ Khan, S., Thornes, J. E., Baker, J., Olson, D. W., & Doescher, R. L. (2010). 'Monet at the Savoy.' Area, 42(2), 208-216. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00913.x

- ↑ Taylor, J. R. (1995). 'Claude Monet impressions of France': from Le Havre to Giverny. London: Collins and Brown.

- ↑ 'Monet’s ‘London Series’ and the Cultural Climate of London at the Turn of the Twentieth Century'. (n.d.). Weather, Climate, Culture. doi:10.5040/9781474215947.ch-008

- ↑ Seiberling, G., & Monet, C. (1988). 'Monet in London.' Atlanta: High Museum of Art.

- ↑ Patin, S., & Monet, C. (1994). 'Claude Monet in Great Britain.' Paris: Hazan.

- ↑ Shanes, E. (1998). Impressionist London. New York: Abbeville P.

- ↑ Interpretive Resource. (n.d.). Retrieved June 21, 2017, from http://www.artic.edu/aic/resources/resource/383

- ↑ Interpretive Resource. (n.d.). Retrieved June 21, 2017, from http://www.artic.edu/aic/resources/resource/383

- ↑ Forge, Andrew, and Gordon, Robert, 'Monet', page 224. Harry N. Abrams, 1989.

- ↑ 'Let the light shine in', Guardian News, 30 May 2002. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ↑ "Monet's Village". Giverny. 24 February 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2012.