British WW2 Codebreaking

From Londonhua WIKI

British WW2 Codebreaking

3 Rotor Enigma Machine | |

| Location | Bletchly Park |

|---|---|

Contents

Abstract

The paragraph should give a three to five sentence abstract about your entire London HUA experience including 1) a summary of the aims of your project, 2) your prior experience with humanities and arts courses and disciplines, and 3) your major takeaways from the experience. This can and should be very similar to the paragraph you use to summarize this milestone on your Profile Page. It should contain your main Objective, so be sure to clearly state a one-sentence statement that summarizes your main objective for this milestone such as "a comparison of the text of Medieval English choral music to that of the Baroque" or it may be a question such as "to what extent did religion influence Christopher Wren's sense of design?"

Introduction

I suggest you save this section for last. Describe the essence of this project. Cover what the project is and who cares in the first two sentences. Then cover what others have done like it, how your project is different. Discuss the extent to which your strategy for completing this project was new to you, or an extension of previous HUA experiences.

As you continue to think about your project milestones, reread the "Goals" narrative on defining project milestones from the HU2900 syllabus. Remember: the idea is to have equip your milestone with a really solid background and then some sort of "thing that you do". You'll need to add in some narrative to describe why you did the "thing that you did", which you'd probably want to do anyway. You can make it easy for your advisors to give you a high grade by ensuring that your project milestone work reflects careful, considerate, and comprehensive thought and effort in terms of your background review, and insightful, cumulative, and methodical approaches toward the creative components of your project milestone deliverables.

Section 1: Background

Enigma

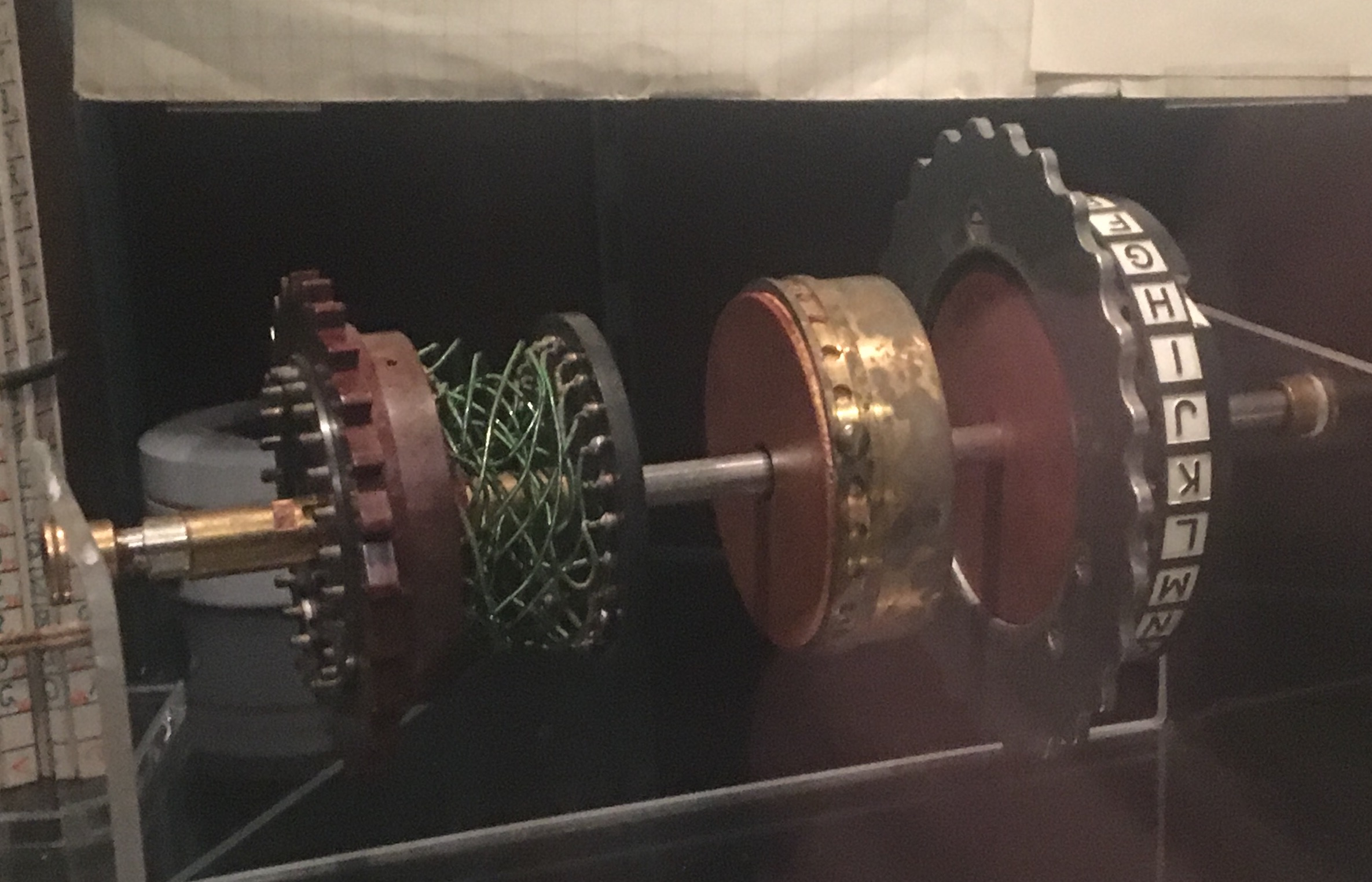

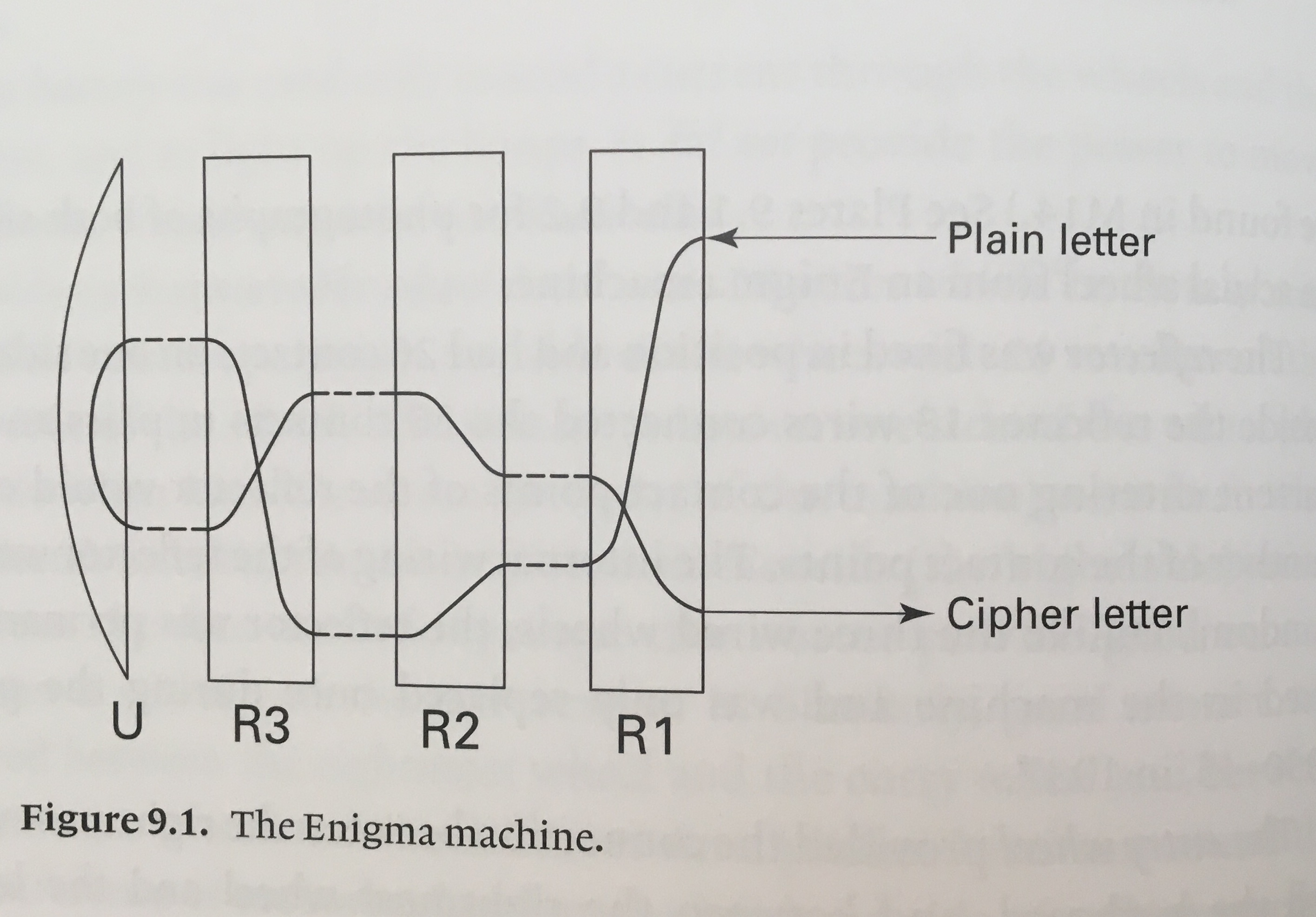

In order for the German Military to communicate with troops on the battlefield and submarines away from base, radio signals were utilized. This was a monumental event, but it did have it's drawbacks. Since it was radio signals the enemy could intercept them. To protect the messages they needed to be enciphered. In the 1920s a German Engineer named Arthur Scherbius designed many different cipher machines. He settled on a design and called it Enigma.[1] This original design for Enigma was based upon a 26 letter keyboard for inputting the plaintext message, 26 lamps to show the cipher letters, a power supply, three removable wired wheels that rotate around a common axis, a fixed reflector, and a fixed entry wheel. How this was set up introduced two important features; no letter can encipher itself, and there is symmetry of plain-cipher pairs, ex. if J enciphers M, then M enciphers J.[2] This scrambling of letters would have been the equivalent of a complex substitution cipher if the wheels didn't move, but they did. Whenever a key was pressed a mechanical mechanism advanced the wheel one position, so after twenty-six key presses the first wheel would return to its starting position. At this point the second wheel would then turn, and once that wheel made a full rotation then the third wheel would turn. This rotating mechanism made the enciphering process very complex as all three wheels would not have returned to their original positions until 16,900 letters would have been enciphered.[3] This rotating motion made deciphering difficult, but several other parts of the machine made things even more sophisticated. One of these was the option to take off the three wheels and reorder them in six different ways, this produced 101,400 different substitution alphabets. To add even more of a challenge for anyone trying to decrypt the messages, the second rotor could be started in any one of its 26 positions which created 105,456 possible starting positions and substitution alphabets, and that's with having an Enigma machine which was the best case scenario.[4]

The German Military did not think this original design provided sufficient protection, so they made some changes to the design for their use. One major modification that they introduced was the plugboard. The plugboard used up to thirteen short cables, the German's used ten, to switch letters at input and output of the machine. If, for example, B was connected to R, then whenever a B was pressed it would go into the rotors as an R, and vice versa. Also if an R came out of the rotors, the B light would turn on, and vice versa.[6] This increased the number of combinations even more, multiplying the already large amount of combinations by 150 million million.[7] Another modification made by the military was the addition of more rotors. They increased the number of rotors available from three to five of which any three could be chosen and put in any order giving 60 possible combinations for the rotor order.[8] Later in the war the Navy wanted more security for their Enigma setup, so a four rotor Enigma machine was developed and distributed. With the addition of an extra rotor slot the number of rotors available to choose from was increased to eight for the Navy. In addition to the additional rotors the Naval message indicators were disguised using a bigram table.[9] In order to determine the indicator these bigram tables needed to be known.

These changes made by the German Military made the number of possibilities unimaginable and theoretically unbreakable, but in use the Germans made several key mistakes. The first large mistake was the double encipherment of the message setting that occurred until May 1940. This allowed the bypassing of the plugboard that ensured the security of Enigma as analyzing 100 messages produced enough indicators to break the encipherment. For use in the Bombe machines, lengthy cribs were needed. This was supplied by Germans diving full titles of the addressee and originator. A third mistake was that operators sent the same message twice using different ciphers that were similar. The laziness of operators were essential and were so common they got their own nickname. One of these was called Sillies, referring to on operator that used his girlfriend's name 'Cilli', which means easy to guess encoding of the message. Another of these techniques was called the Herivel Tip which relied upon the operator not randomizing the key to encrypt the message from the ground setting for the day which led to patterns and allowed 17,576 to be reduced to something like 30. There were many techniques used from the German's improper use of the machine to break into Enigma with many coming from different people who spotted different patterns or had different ways of thinking about what the German operators were doing. In the end this payed off and allowed for many German messages to be decrypted throughout the war.[10]

To set up an Enigma Machine[11]

1) The Operator would consult the list provided for the day's ground settings and turn the rotor's ring to those positions

2) The Operator would choose three random letters as the start position to encipher the message with

3) The Operator would then encode the start position twice (once after 1940)

4) The Operator would turn the rotors to the start position and encode the message

5) The radio operator then would transmit the encoded message using Morse code

To break Enigma[12]

1) Intercept Morse code signals using Y stations

2)

3)

Translated to English

Analyzed for intelligence worth and possibly passed up chain of command

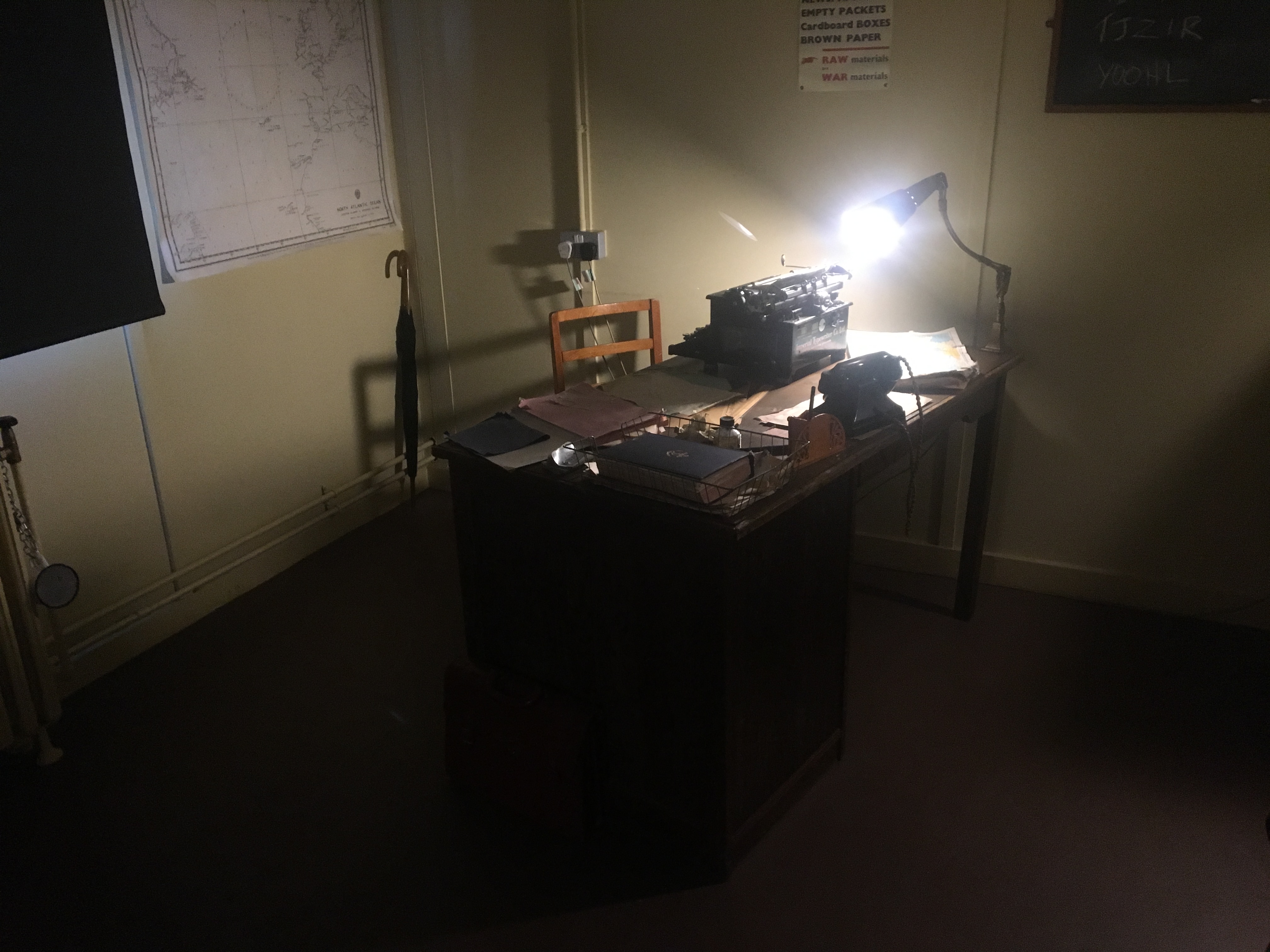

Bletchley Park

As war approached Britain was preparing for another world wide war. One part of this were secret intelligence groups know as MI6 and GC&CS, Government Code and Cypher School. During the war the central location for this type of intelligence needed to be protected while still being in the proximity of London, Bletchley Park was a option and was the one chosen to host it.[13] In the beginning it was not a very large operation as it consisted of the Mansion and its outbuildings with about 150 staff.[14] As the operation was expanded and began breaking German Enigma codes resources were still lacking. After appealing the Winston Churchill a major building program began including Blocks for the workers and outhouses to house the Bombe machines.[15] In the end dozens of buildings were built, each with their own purpose but only known by their Hut number in the name of secrecy. Below is a list of key buildings and their purpose, there are more but these are the most important. Also below are before and after pictures of Bletchley Park which shows the massive expansion that occurred.

Buildings

- Mansion - The Mansion was the main building of the initial site and housed many different groups throughout the war. The Intelligence Exchange group was housed here until it was moved to Hut 4. Most other rooms were used as offices and record keeping storage rooms.[16]

- Hut 3 - Hut 3 was the intelligence hut for German Army and Air Force communications after having been processed by Hut 6. In February of 1943 the Hut 3 reporting group was moved to Block D and the buildign was renamed Hut 23.[17]

- Hut 6 - Hut 6 housed the Enigma processing machinery for the German Army and Air Force messages who then passed the information onto Hut 3 for translation and reporting. In February 1943 the Hut 6 Section moved to Block D and the building was renamed Hut 16.[18]

- Hut 8 - Hut 8 was dedicated to the breaking of the German Naval Enigma Messages. It was here that Alan Turing lead his team in breaking the Naval Enigma codes. In February of 1943 the Hut 8 Naval Enigma processing section moved to Block D and the building was renamed Hut 18.[19]

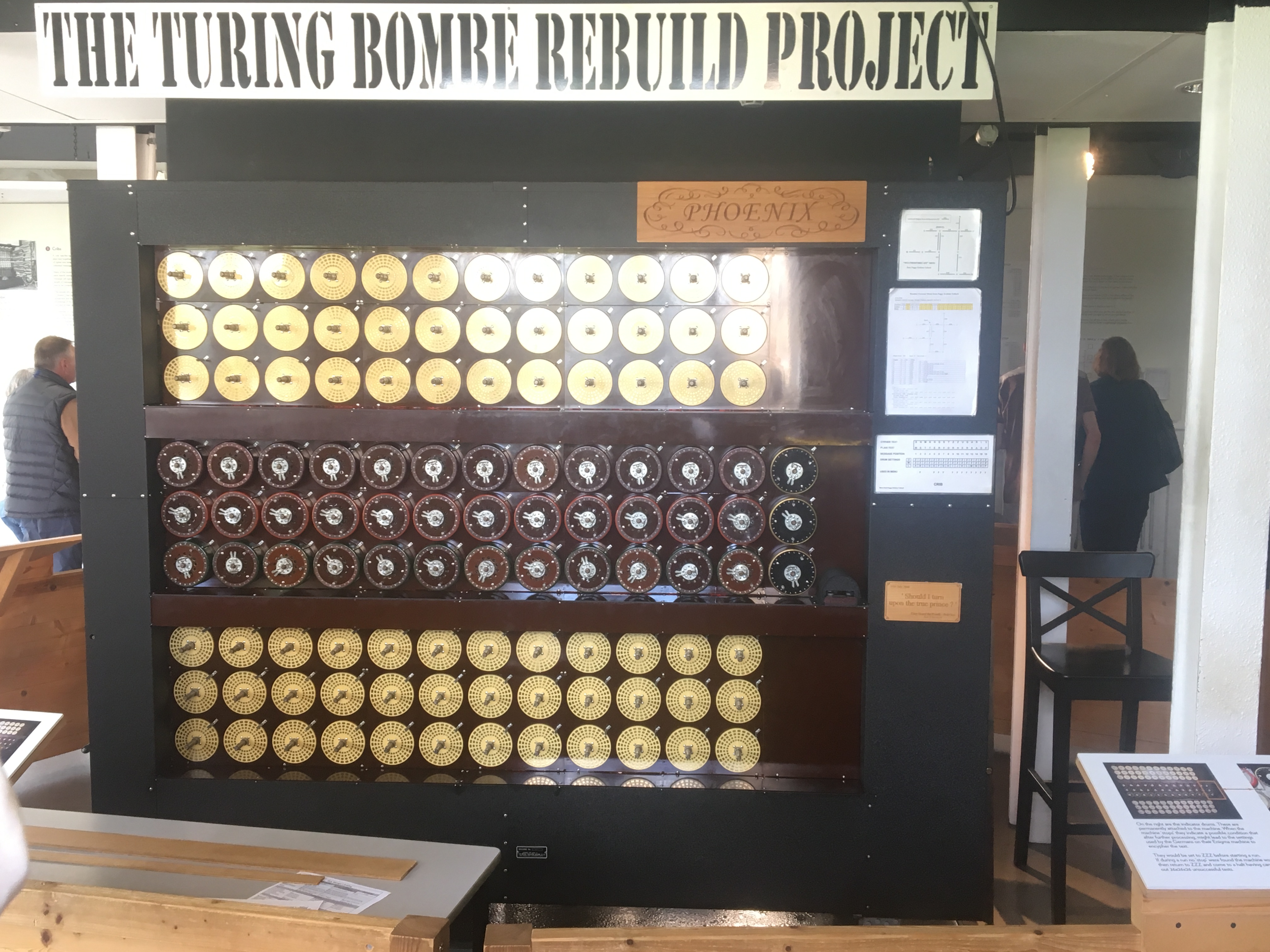

- Hut 11 - Hut 11 housed the original Bombe Machines that were co-designed by Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman. It was here that the WRENS, Women's Royal Naval Service, worked in teams of two to set up the machines according to the menus they were given to find possible settings for the day's Enigma settings. These machines were eventually moved to Hut 11A so Hut 11 could be used to test new equipment being designed including Rob and Colossus.[20]

- Block D - Block D was completed in January of 1943 as a one story building to be completed more quickly than the original two story design. Here Huts 3, 6, and 8 were housed in 40,000 square feet which at the time of completion the largest building at Bletchley Park. To protect the building a weapons tower with machine guns was built on the roof to repulse any low-flying enemy aircraft.[21]

Alan Turing

Who is Alan Turing, what did he do, and how did he do it

Gordon Welchman

Gordon Welchman before the war was a Algebraic Geometry professor at Sidney Sussex College. As the war began he was asked to assist with code breaking for intelligence at Bletchley Park. While there he headed up Hut 6 focused on braking the German Army and Air Force codes while also offered ideas in how to improve the efficiency of the process to help scale up the code breaking process. To do this more talent was needed, with his connections to colleges he recruited from the Cambridge area colleges.[22] While he and his team worked to break Enigma with the hand technique developed by the Poles, the Germans changed their protocol. Previously the starting position for the message was enciphered twice at the beginning of the message which was changed to only be enciphered once. This change made the previous method worthless and new ideas had to be thought of.[23] With Alan Turing's machine built and installed it was supposed to be the savior of the code breaking operation, but it didn't really work. It had too many false positives and took far too long to be useful. After hearing about Turing's idea behind the machine Welchman came up with another idea. It was called the diagonal board. The process of code breaking was based upon educated guesses, and if that guess is wrong the Bombe just kept searching which lead to it taking a very long time to find a solution. This diagonal board solved this problem by simultaneously scanning all possible combinations by allowing an unlimited number of reentries into the chain.[24] If a wire became live then there were up to 25 more possible false inputs that could also be checked to rule out that configuration.[25] This allowed the Bombe to find the solution magnitudes faster than previously.

Bombe

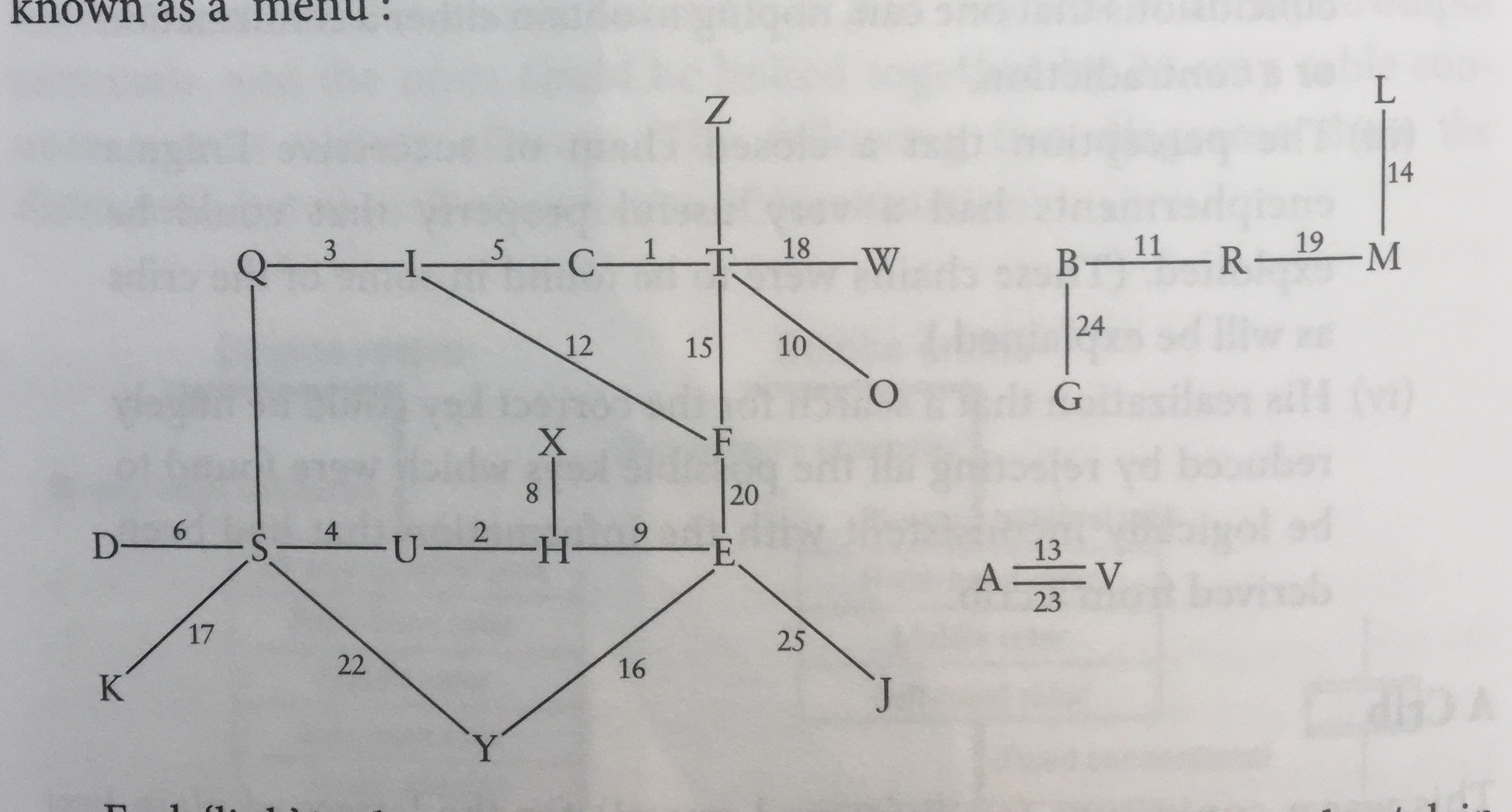

In the multi-step process of breaking Enigma the Bombe was essential. All parts of the process were important but without the Bombe doing automated checking Enigma would have stayed unbreakable. The purpose of the Bombe was to utilize a crib, likely plain-text message, to check the 17,576 possible configurations of the rotors, which it did in about 10.5 minutes.[26] To set up a Bombe cryptographers created a menu which was formed from a plausible plain-text message. If the guess was correct the Bombe would stop giving the codebreakers a plausible starting position for the rotors and one of the plugboard connections.[27] To solve the rest of the plugboard connections a checking machine was used. The checking machine works the same way as an Enigma machine without the plugboard. Using a combination of the menu, starting positions from the Bombe, and the first plugboard connection from the Bombe all the others can be deduced with the checking machine. If there are contradicting letters than the Bombe gave a false stop and has to be restarted.[28]

To create a menu a crib was lined up with the cipher-text and as no letter can be enciphered as itself a plausible relationship between the two could be made. If X was the sixth position of plain-text and O was the sixth position of cipher-text then it's possible that when the rotors had moved six places from the start X is enciphered as O.[29] This was done many times and created loops of letters enciphering each other. These loops when combined created a menu used to break enigma. The drums on the front of the Bombe rotated checking for the rotor positions. On the back of the machine were miles of wires connected between different letters to use these menus to remove false positives from the system.[30]

With the German Navy increasing the number of rotors to four the existing Bombe machines were modified to try and solve it, but were unable to. A special four rotor Bombe had to be designed to break the four rotor Enigma.[31] It was based upon the same concepts as the three rotor Bombe but included another row of rotors and was optimized for the four rotor job.

The Impact

The impact of the cracking Enigma, what it did for the British and the Allies, and the impact it has had on encryption

Section 2: Deliverable

Enigma Recreation

Virtual recreation of an enigma machine

The Math behind it

Math behind the Enigma machine and showing why it was such a difficult problem

| Enigma Type | Rotor States | Wheel Orders | Plug Board | Total Combinations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | 263 | 3*2*1 | 1 | 105,456 |

| Army and Air Force | 263 | 5*4*3 | 26!/10!6!210 | 158 billion billion |

| Naval | 264 | 8*7*6*5 | 26!/10!6!210 | 115,724 billion billion |

Gallery

Conclusion

In this section, provide a summary or recap of your work, as well as potential areas of further inquiry (for yourself, future students, or other researchers).

References

- ↑ Churchhouse, R. (2002). Codes and ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge University Press. pp 111.

- ↑ Churchhouse, R. (2002). Codes and ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge University Press. pp 112-115.

- ↑ Churchhouse, R. (2002). Codes and ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge University Press. pp 119.

- ↑ Churchhouse, R. (2002). Codes and ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge University Press. pp 119-120.

- ↑ Churchhouse, R. (2002). Codes and ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge University Press. pp 114.

- ↑ Churchhouse, R. (2002). Codes and ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge University Press. pp 121.

- ↑ Greenberg, J. (2014). Gordon Welchman: Bletchley Park's Architect of Ultra Intelligence. Frontline Books. pp 213.

- ↑ Turing, D. (2014). Bletchley Park Demystifying the Bombe. pp 6.

- ↑ Turing, D. (2014). Bletchley Park Demystifying the Bombe. pp 59.

- ↑ Welchman, G. (1982). The Hut Six Story: Breaking the Enigma Codes. Penguin Books. pp 164-167.

- ↑ Churchhouse, R. (2002). Codes and ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge University Press. pp 123.

- ↑ Welchman, G. (1982). The Hut Six Story: Breaking the Enigma Codes. Penguin Books. pp 149-161

- ↑ Storm Clouds Gather. (n.d.). Retrieved May 26, 2017, from [1]

- ↑ Cottage Industry. (n.d.). Retrieved May 26, 2017, from [2]

- ↑ Intelligence Factory. (n.d.). Retrieved May 26, 2017, from [3]

- ↑ Bonsall, A. (2009). History of Bletchley Park Huts & Blocks 1939-45. pp 27-32.

- ↑ Bonsall, A. (2009). History of Bletchley Park Huts & Blocks 1939-45. pp 8-9.

- ↑ Bonsall, A. (2009). History of Bletchley Park Huts & Blocks 1939-45. pp 11.

- ↑ Bonsall, A. (2009). History of Bletchley Park Huts & Blocks 1939-45. pp12.

- ↑ Bonsall, A. (2009). History of Bletchley Park Huts & Blocks 1939-45. pp 14.

- ↑ Bonsall, A. (2009). History of Bletchley Park Huts & Blocks 1939-45. pp 24.

- ↑ Greenberg, J. (2014). Gordon Welchman: Bletchley Park's Architect of Ultra Intelligence. Frontline Books. pp 31-35.

- ↑ Greenberg, J. (2014). Gordon Welchman: Bletchley Park's Architect of Ultra Intelligence. Frontline Books. pp 43.

- ↑ Greenberg, J. (2014). Gordon Welchman: Bletchley Park's Architect of Ultra Intelligence. Frontline Books. pp 63.

- ↑ Turing, D. (2014). Bletchley Park Demystifying the Bombe. pp 38.

- ↑ Turing, D. (2014). Bletchley Park Demystifying the Bombe. pp 10, 12.

- ↑ Turing, D. (2014). Bletchley Park Demystifying the Bombe. pp 11.

- ↑ Turing, D. (2014). Bletchley Park Demystifying the Bombe. pp 43-47.

- ↑ Turing, D. (2014). Bletchley Park Demystifying the Bombe. pp 14.

- ↑ Turing, D. (2014). Bletchley Park Demystifying the Bombe. pp 23.

- ↑ Turing, D. (2014). Bletchley Park Demystifying the Bombe. pp 61.

- ↑ Greenberg, J. (2014). Gordon Welchman: Bletchley Park's Architect of Ultra Intelligence. Frontline Books.