Impact of the RAF on the Battle of Britain

From Londonhua WIKI

(Redirected from Impact of the RAF on WW2)

Impact of the Royal Air Force on the Battle of Britain

Contents

- 1 Impact of the Royal Air Force on the Battle of Britain

- 2 Abstract

- 3 Introduction

- 4 Section 1: Background

- 5 Section 2: Deliverable

- 6 Conclusion

- 7 References

Abstract

This milestone is about the Royal Air Force, its major effect on the Battle of Britain, and how they were able to accomplish this task. It looks at the technical details of the aircraft from both Britain and Germany, that I obtained from the Royal Air Force museum, then moves into the British Fighter Command structure. This command was essential and how it operated proved vital during the Battle of Britain. The deliverable then shows this Fighter Command structure visually in an interactive animation. Previously, I have taken two History courses with one of them being on World War II so I do have some previous background. My main takeaway from my experience with this milestone is that it is very impressive how many forces the British were able to coordinate to defend the country with such short notice of incoming aircraft.

Introduction

This milestone covers the Royal Air Force, RAF, and its impact on the Battle of Britain during World War II and how it was technically able to have this impact. This topic is very important, as without the RAF holding off the Luftwaffe, Britain would have been invaded in short time. I'm sure many people have covered British Fighter Command and the Battle of Britain but building up a background and displaying it in an interactive visual animation is something I think is special to my project and makes it unique. I have studied the Battle of Britain on a large scale in the 20th Century American Foreign Relations course at WPI, but we did not cover the inner workings of the RAF and its defense.

Section 1: Background

Aircraft Production Ramp up

After the breakup of the League of Nations' Disarmament Conference in 1934, Britain began its expansion of its Air Force. This first expansion announcement was known as 'Scheme A'. Shortly after this announcement Britain's Secretary of State for air, Sir Philip Cunliffe-Lister, increased the expansion program.[2] The goal for the program was to increase the RAF, Royal Air Force, by 588 aircraft to include a total of 1512 aircraft. To make the goal a reality, the Shadow Factory scheme was put into place in March 1936. This program built state owned plants that were managed by non-aerospace industrial manufacturers who built products designed by aircraft makers.[3] One example, Lord Huffield's company, Wolseley, was given control of the Castle Bromwich factory that built Spitfires under the guidance of Vickers Supermarine. In the end, Huffield's company was very inefficient at running the factory which was then turned over to Vickers Supermarine directly to manufacture Spitfires. This was an instance of the Shadow factory scheme not working well and hurt Britain at the beginning of the Battle of Britain because of the limited number of Spitfires that were available. Other manufacturers also had issues, but some excelled at their duties, it was a mixed bag of performances. The important part was to get as many aircraft ready to fly as possible to thwart the oncoming German aggression.[4] Below is the technical descriptions of the main aircraft used on both the British side and German side during the Battle of Britain to show how the aircraft would perform against one another in combat.

British Royal Air Force

Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim was a two seater night fighter that was converted from the original design of a light bomber. Powering the plane were two 840 hp Bristol Mercury VIII radial piston engines. It had a maximum speed of 260 mph at 12,000 ft, with a service ceiling of 24,600 ft. It had a range of 1,460 miles on its internal tanks. The empty weight of the plane was 8,100 lbs with a maximum takeoff weight of 12,500 lbs. it had a wingspan of 56 ft 4 in, a length of 39 ft 9 in, and a height of 12 ft 10 in. It was armed with six 0.303 in machine guns.[6]

Variants

Blenheim Mk I

Blenheim Mk IF

Blenheim Mk IV

Blenheim Mk IVF

Blenheim Mk V

Defiant

The Boulton Paul Defiant was a two seater fighter. It was powered by a 1,030 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin III twelve cylinder liquid cooled engine. It had a maximum speed of 304 mph at 17,000 ft with a service ceiling of 30,348 ft. It had a maximum range of 465 miles. Its empty weight was 6,281 lbs with a maximum takeoff weight of 8,424 lbs. It had a wingspan of 39 ft 4 in, a length of 35 ft 4 in, and a height of 11 ft 4 in. It was armed with four 0.303 in Browning machine guns mounted to a hydraulically operated turret behind the pilot. The turret allowed for exceptional coverage but being a heavier aircraft it was sluggish in combat and was vulnerable to conventional enemy fighters. After several massacres at the hands of the Luftwaffe the fighter transitioned into a Night Fighter but when that wasn't successful either the fighter was phased out.[8][9][10]

Variants

Defiant Mk I

Defiant NF.Mk I

Defiant TT.Mk I

Defiant NF.Mk II

Defiant TT.Mk II

Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane was a single seater fighter/fighter-bomber. It was powered by one 1,280 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin XX V-12 piston engine. It had a maximum speed of 342 mph at 22,000 ft with a service ceiling of 36,500 ft. The range of the plane was 480 miles with internal tanks, but also had external tanks with a capacity of 90 gallons which about doubled this range. The empty aircraft weighed in at 5,500 lbs, with a maximum take-off weight of 7,300 lbs. The plane had a wingspan of 40 ft, length of 32 ft 2 1/2 in, and a height of 13 ft 1 in. It was armed with twelve 0.303-in forward-firing machine-guns, plus two 250 lb or one 500 lb bombs. The later versions of this aircraft replaced the twelve 0.303-in machine guns with four 20 mm cannons.[11]

Variants

Hurricane Mk I

Hurricane Mk II

Hurricane Mk III

Hurricane Mk IV

Hurricane Mk V

Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire was a single seater day fighter. It was powered by a 1,030 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin II or III V-12 piston engine. It had a maximum speed of 355 mph at 19,000 ft with a service ceiling of 34,000 ft. It had a maximum range of 495 miles on its internal tanks. Empty it weighed in at 4,796 lbs with a maximum takeoff weight of 5,332 lbs. It had a wingspan of 36 ft 10 in, a length of 29 ft 11 in, and a height of 11 ft 5 in. It was initially armed with 8 0.303-in Browning machine guns, but later on in the war 20 mm Hispano cannons were introduced. There were several different wing designs throughout its lifetime that were used to house different weapons. The original A wing housed eight 0.303-in machine guns, the B wing housed four 0.303-in machine guns and two 20 mm cannons, and the C wing was interchangeable and could be formatted like the previous A and B wings or a third option of four 20 mm cannons.[12] Later in the war more wing variants were developed, the D wing was a specialized wing for photo reconnaissance aircraft providing extra fuel to allow for a range of up to 2000 miles, the E wing housed two 20 mm and two 0.5 in cannons as well as the capacity to hold a 250 lb bomb on each wing.[13][14]

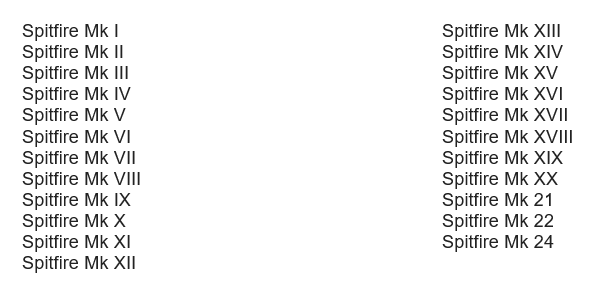

Variants

German Luftwaffe

Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 was a single seater multirole fighter. It was powered by a 1,200 hp Daimler-Benz DB 605A liquid cooled 12 cylinder piston engine. It had a maximum speed of 359 mph and a service ceiling of 36,499 ft. It had a maximum range of 680 miles. When empty it had a weight of 4,440 lbs and a maximum takeoff weight of 6,100 lbs. It measured 32 ft 4 in in wingspan, 28 ft 8 in in length, and 11 ft 2 in in height. For armament it had a cannon in the propeller hub, two to four 7.9 mm machine guns, and two cannons in underwing gunpods.[15]

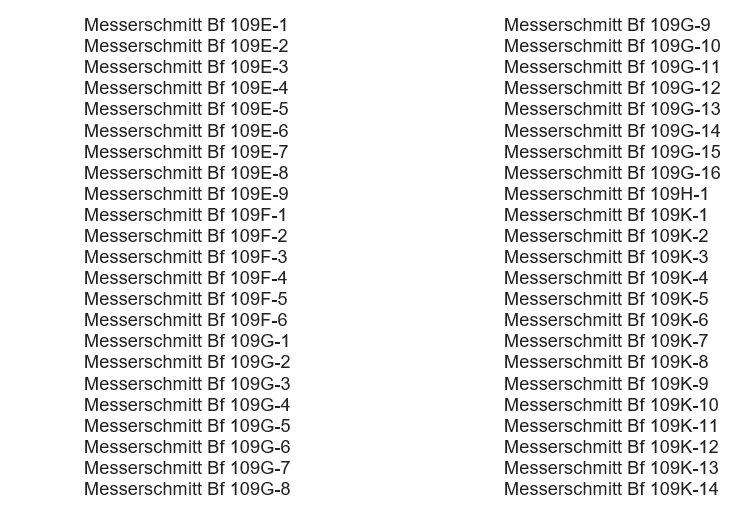

Variants

Messerschmitt Bf 110

The Messerschmitt Bf 110 Zestorer was a two seater Heavy Fighter/Fighter-bomber. It was powered by two Daimler Benz DB 601B-1 V-12 piston engines producing 1,474 hp. It had a maximum speed of 342 mph with a service ceiling of 26,247 ft. It had a maximum range of 1,305 miles. The empty weight of the aircraft was 11,222 lbs with a maximum takeoff weight of 21,804 lbs. It had a wingspan of 53 ft 4 in, a length of 42 ft 9 in, and a height of 13 ft 8 in. It was armed with two 30 mm and two 20 mm cannons in its nose and two 7.92 mm machine guns in the rear cockpit. The fighter bomber versions could also carry up to 4,410 lbs of conventional drop bombs. The aircraft excelled at its main design point of being a combat destroyer, but maneuverability was its weakest quality.[16]

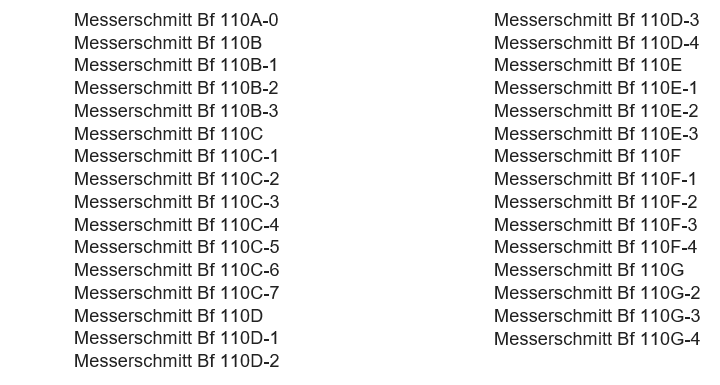

Variants

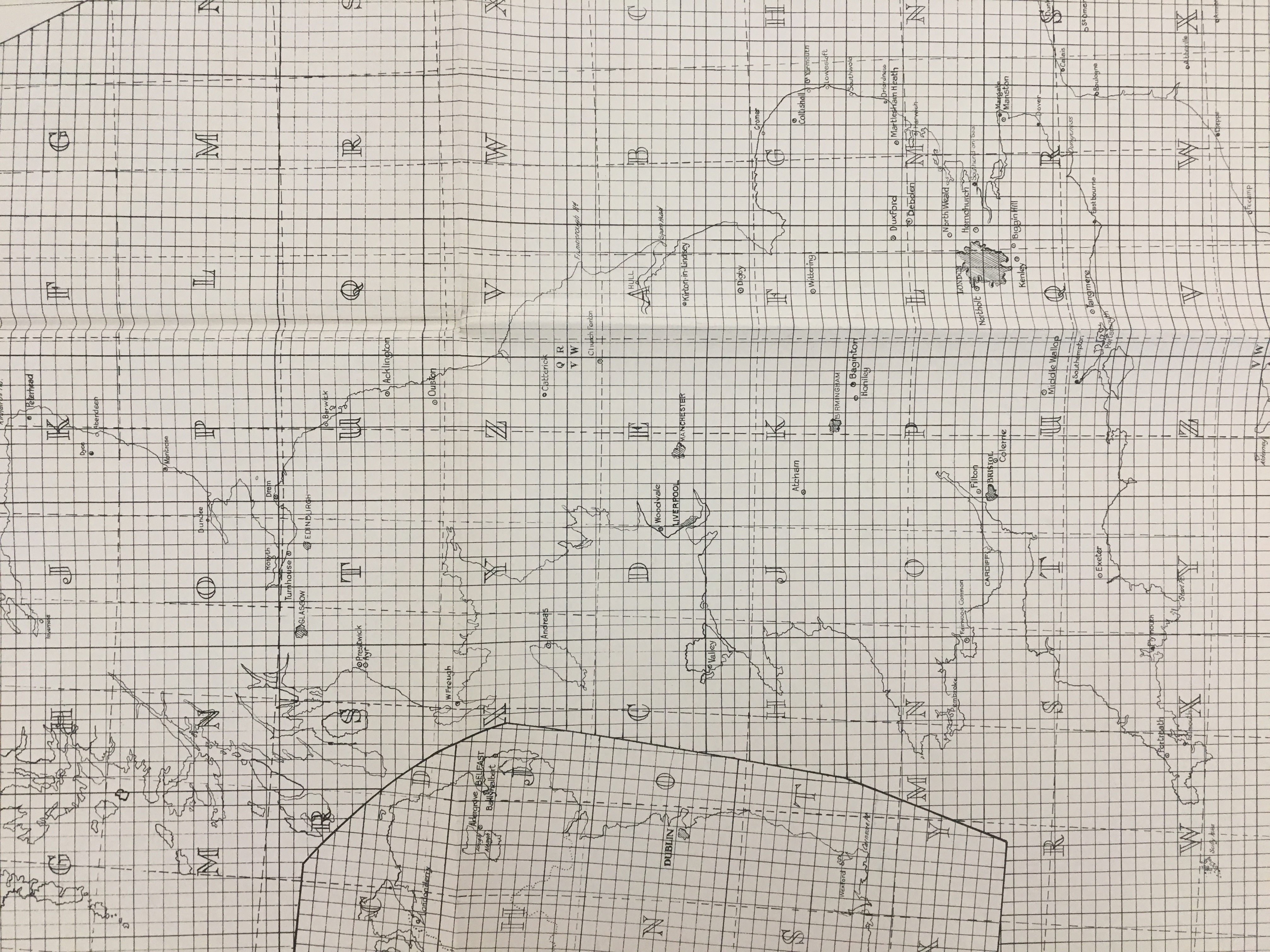

British Fighter Command

The Fighter Command's Commander-in-Chief during the lead up to and during the Battle of Britain was Sir Hugh Dowding.[18] The role of Fighter Command was to repel any attack on Britain from the Luftwaffe, German Air Force. To best complete this mission Dowding had a plan to divide his resources across England. The No. 11 group which covered the southeast of the country was supplied with 12 Hurricane, 6 Spitfire, and 4 Blenheim squadrons. The No. 12 group which covered the East Anglia area was supplied with 5 Hurricane, 5 Spitfire, 2 Blenheim, and 1 Defiant squadrons. The No. 13 group in the north was supplied with 3 Hurricane, 6 Spitfire, 1 Blenheim, and 1 Defiant squadrons. The No. 10 covering the west included 2 Hurricane, and 2 Spitfire squadrons. Many people felt that Dowding should have concentrated all of his best fighters in the No. 11 group as that was the most likely to encounter fighter opposition. Dowding knew that the Battle of Britain would be a war of attrition and to keep a mix of fighters in less dangerous areas as a reserve would be important to the upcoming battle.[19] The Fighter Command had plenty of aircraft to go around with production ramping up, but pilots were much more difficult to replace. At the beginning of the Battle of Britain many squadrons were over-manned but as it dragged on training new pilots became a problem. As training took 6 months there were not enough pilots to have Fighter Command at full strength so the training courses were reduced to 4 weeks with the squadrons left to finish the pilot's training, sometimes with disastrous consequences.[20] Dowding was not the most liked of the leaders in the military and was eventually forced out of his position as the head of Fighter Command on November 17, 1940.[21] At the time, no one recognized the importance of his work and how he saved Britain. Most importantly he set up a system of direction and control for his fighters to get the most out of their limited resources. Second, Dowding pushed to limit the support of the French in terms of aircraft that were essential to defending Britain in an air attack; he didn't stop the outflow of aircraft but helped reduce the number of aircraft supplied to France. Third, his careful placement and use of fighter resources prevented being draw into a major battle and having his forces destroyed. His plan to keep fighters in reserve to reinforce the main No. 11 group was essential to this even though it gained much criticism.[22]

Fighter Command and Control System

Radar Stations

At the time Radar was known as Radio Direction Finding and the system that was in use by the British was simple but effective. The initial deployment was High Frequency Radio Direction Finding (HF DF) to find the position of a friendly aircraft when it was out of sight of the controller. As the technology became refined, Fighter Command began experimenting with radar controlled intercepts of unknown targets in 1936.[24] In 1937, the system in use was known as Pip Squeak. This system transmitted a coded DF signal for 14 seconds every minute to allow the controllers to know the identity of each aircraft. To identify the other aircraft not using the Pip Squeak system they turned to physicist Robert Watson-Watt. This new technology was designated RDF which was rapidly developed. In only a few months the system was up and running detecting aircraft out to 58 miles. A string of these radar stations were built on the southern coast in 1936 and became fully operational in 1938.[25] This first chain of 21 stations was called Chain Home and utilized fixed antenna arrays. There was also another set of radar stations called the Chain Home Low stations, of which there were 30, that utilized a rotating antenna for a narrow search beam. These were not as effective as they had less range and could not provide altitude information.[26] In addition to these radar advances, an improvement in plane identification was also being developed. The new system was called IFF, Identification Friend or Foe. The IFF was a small transmitter that produced a distinctive radar blip to allow radar operators to differentiate between friend and foe.[27] When both friendly and enemy planes were spotted on radar that information was then sent to the Filter Room to be assessed.

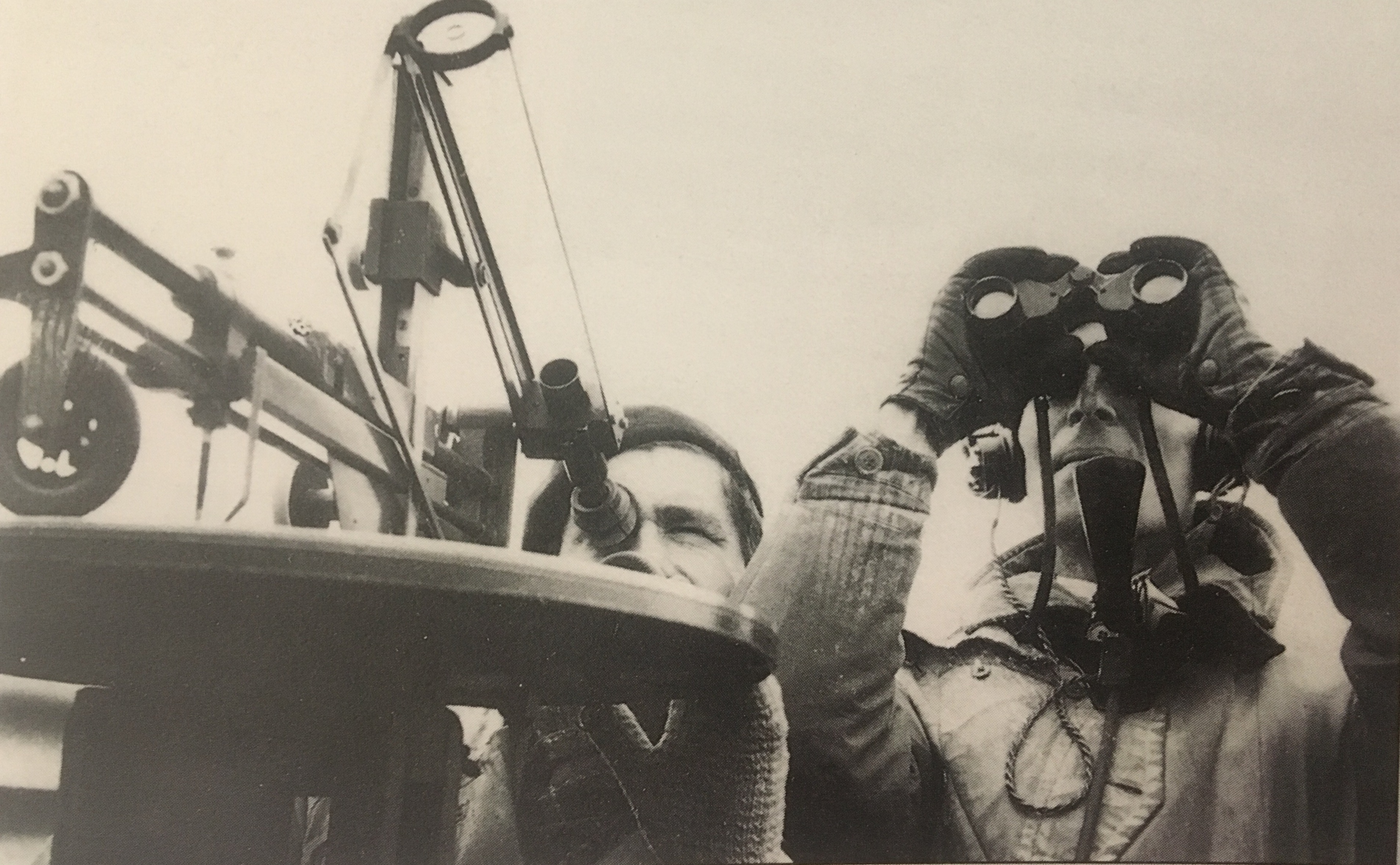

Observer Corps

The Observer Corps was a volunteer service meant to fill in the gaps of radar. Radar was successful at looking out to sea but was blind to its back on land. The job of the Observer Corps was to track and report the movement of aircraft over land. Volunteers for the Observer Corps used binoculars, telescopes, and makeshift devices to determine the altitude and bearing of enemy aircraft. This technique was trialed in 1925 to outstanding success, after which the program rolled out rapidly to over 100 posts in that year. For the large roll out, a map was divided into 1.2 mile squares which then reported via telephone lines to their respective Observer Corps Group Headquarters. The full scale system across Britain was tested during the 1939 Air Exercises after which the posts were manned unbroken for 6 years until the end of the war.[29]

Fighter Command Operations Room and Filter Room

The Fighter Command and Operations Room was manned by the Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command, Commander-in-Chiefs of the Observer Corps and the Anti-Aircraft Command, the liaison officers of Bomber and Coastal Commands, the liaison officer of the Admiralty, and the liaison officer for the Ministry of Home Security. The room housed the plotting table that displayed aircraft over all of the UK and the sea approaches. The Filter Room was located underneath the Fighter Command Operations Room. Its job was to receive all of the plots from the Radar Stations, compile them and cross reference the plots with the IFF plots. These cross referenced plots were then passed upstairs to the Fighter Command Operations Room.[31]

Group and Sector Operations Rooms

The Group Operations Room received radar plots from the Filter Rooms and visual plots from the Observer Corps. The information was analyzed and then used to direct sectors to deal with incoming raids. In the event the Group Operations Room was knocked out in a raid, each Sector Operations Room could be used as the command center. Each Sector Operations Room had its own plotting tables with radar and Observer Corps plots provided from the Filter Room. When a Sector Operations Room was given notice of an enemy raid, a controller would order an aircraft launch and then vector them for an intercept, which was confirmed when the formation leader called 'Tally Ho!' which means enemy in sight.[32] To vector the aircraft, the controller needed to know the location of the friendlies which was reported by the Direction-finding Triangulation who received information from the Direction Finding, D/F, stations. The Sector Operations Room also controlled the anti-aircraft guns and Balloon Barrages. As with the aircraft launches, the Sector Controller would alert the guns and balloons to incoming enemy raids to allow them time to get into position.[33]

Section 2: Deliverable

As the background has covered the RAF and its command structure during the Battle of Britain in writing, the below deliverable illustrates this system through an animation to really show how it worked. The command structure was much more vast than the animation covers but it does take the essential parts and simplify it to more easily illustrate the command system.

For the animation Click here.

Conclusion

This milestone background covered the process of the preparation of the RAF prior to World War II, how the RAF was able to withstand the Luftwaffe onslaught during the Battle of Britain, and the details of the technical workings of the RAF aircraft and command structure and the German aircraft. A key part of the entire British system was the many levels of command that divided the massive area of the country yet were able to keep information flowing quickly and effectively to respond to threats. The deliverable then went on to show this command structure in a visual animation to help illustrate how it operated.

A potential future inquiry could be how the German command structure differed from the British and how that led to their failure in defeating the British.

References

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 175.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 75.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 76.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 77-78.

- ↑ Gunston, B. (1982). British Fighters of World War II. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp 18.

- ↑ Gunston, B. (1982). British Fighters of World War II. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp 18.

- ↑ Gunston, B. (1982). British Fighters of World War II. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp 16.

- ↑ Boulton Paul Defiant. (n.d.). Retrieved June 09, 2017, from [1]

- ↑ J. (2015, May 26). 9 Iconic Aircraft From The Battle Of Britain. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from [2]

- ↑ Boulton Paul Defiant Night-fighter / Interceptor Aircraft. (n.d.). Retrieved June 09, 2017, from [3]

- ↑ Gunston, B. (1982). British Fighters of World War II. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp 10.

- ↑ Gunston, B. (1982). British Fighters of World War II. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp 13.

- ↑ Rickard, J. (2007, March 12). Supermarine Spitfire - the gun wings. Retrieved June 09, 2017, from [4]

- ↑ Gunston, B. (1982). British Fighters of World War II. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp 46.

- ↑ Messerschmitt Bf 109 Single-Seat Multirole Fighter. (n.d.). Retrieved June 09, 2017, from [5]

- ↑ Messerschmitt Bf 110 Zerstorer (Destroyer) Heavy Fighter / Fighter-Bomber / Night Fighter. (n.d.). Retrieved June 09, 2017, from [6]

- ↑ Great Britain. Royal Air Force. Fighter Command. (1941). Gnomonic Chart with Fighter Command Grid super imposed.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 83.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 90.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 91.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 99.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 93-97.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 97.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 100.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 103-104.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 104.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 104.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 112.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 109-111.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 98.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 105.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 105-106.

- ↑ RAF. (n.d.). RAF - The RAF Fighter Control System. Retrieved June 07, 2017, from [7]