Modern Galleries in London: a Documentary

From Londonhua WIKI

Galleries in London

by Sofia Reyes and Jacob Dupuis

|

A Documentary |

Contents

Abstract

Introduction

I suggest you save this section for last. Describe the essence of this project. Cover what the project is and who cares in the first two sentences. Then cover what others have done like it, how your project is different. Discuss the extent to which your strategy for completing this project was new to you, or an extension of previous HUA experiences.

Section 1: Background

History of Documentary

The documentary film can be regarded as the first genre of the cinema. During the 1890s, when the cinema came into existence, most viewers saw some kind of actuality' film. These early documentaries were often simple, single-shot affairs, showing newsworthy events, scenes from foreign lands, or everyday events. However, more fictional (or staged) actualities also began to be produced from the earliest years of the cinema, based on the special effects capacity of the cinema. An example here might be the Lumiere brothers' Arroseur arrose, which appeared as early as 1895, but per- haps the most well known is Georges Melies' Trip to the Moon (1902) Between 1895 and 1905 a number of identifiable genres of documentary film emerged, including topicals 'travelogues scenics', industrials sports films trick' films fantsy' films, and films that used fictional recon struction or staging in a variety of ways. These early genres of documentary film were quickly assimilated into existing modes of popular culture and entertainment and initially appeared in venues that used other, non-filmic, forms of performance such as acrobatics, song, and dance. [1]

Since the early 1900s, filmmakers have been capturing and telling the stories of real people, places, and events along side fictional ones. The desire to learn or experience something new through film was growing. In 1926, John Grierson, a Scottish filmmaker and expert, created the term Documentary, when reviewing the film Moana, by American filmmaker Robert Flaherty.[2] John Grierson was inspired by the works of Flaherty, and went on to create his own films in Scotland and Britain. He inevitably became in charge of the British Empire Marketing Board where he would oversee production of thousands of films produced in the United Kingdom. In 1929 he developed his own film Drifters, which would then be credited as the first British documentary, introducing the storytelling medium to the English.[3]

While documentary film is a popular informative method of filmmaking, often the difficulty and work put in to create these films is overlooked by the audience. With the rise of smaller, high quality cameras, and better editing capabilities, documentary is becoming even more widespread than ever and still is a popular field for award-winning productions to develop.

Types of Documentary

Every documentary has its own distinct voice. Like every speaking voice, every cinematic voice has a style or “grain” all its own that acts like a signature or fingerprint. It attests to the individuality of the filmmaker or director or, sometimes, to the determining power of a sponsor or controlling organization. Individual voices lend themselves to an auteur theory of cinema, while

shared voices lend themselves to a genre theory of cinema. Genre study

considers the qualities that characterize various groupings of filmmakers

and films. In documentary film and video, we can identify six modes of representation

that function something like sub-genres of the documentary

film genre itself: poetic, expository, participatory, observational, reflexive,

performative.

These six modes establish a loose framework of affiliation within which

individuals may work; they set up conventions that a given film may adopt;

and they provide specific expectations viewers anticipate having fulfilled.

Each mode possesses examples that we can identify as prototypes or mod-

99

Nichols, Intro to Documentary 8/9/01 10:19 AM Page 99

els: they seem to give exemplary expression to the most distinctive qualities

of that mode.They cannot be copied, but they can be emulated as other

filmmakers, in other voices, set out to represent aspects of the historical

world from their own distinct perspectives.[4]

To some extent, each mode of documentary representation arises in

part through a growing sense of dissatisfaction among filmmakers with a

previous mode. In this sense the modes do convey some sense of a documentary

history.The observational mode of representation arose, in part,

from the availability of mobile 16mm cameras and magnetic tape recorders

in the 1960s. Poetic documentary suddenly seemed too abstract and expository

documentary too didactic when it now proved possible to film everyday

events with minimal staging or intervention.

Poetic Documentary

'Subjective and Arttistic Expression'

Poetic Mode: emphasizes visual associations, tonal or rhythmic qualities,descriptive passages, and formal organization. This mode bears a close proximity to experimental, personal, or avant-garde filmmaking.

Poetic documentary can be compared with the Modernist Avant-garde. This type of documentary sacrifices the conventions of continuity editing and the sense of a very specific location in time and place that follows from it to explore associations and patterns that involve temporal rhythms and spatial juxtapositions. Social actors seldom take on the full-blooded form of characters with psychological complexity and a fixed view of the world. People more typically function on a par with other objects as raw material that filmmakers select and arrange into associations and patterns of their choosing.

|

The poetic mode is particularly adept at opening up the possibility of alternative forms of knowledge to the straightforward transfer of information, the prosecution of a particular argument or point of view, or the presentation of reasoned propositions about problems in need of solution.This mode stresses mood, tone, and affect much more than displays of knowledge or acts of persuasion. The rhetorical element remains underdeveloped.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Play of Light: Black, White, Grey (1930), for example, presents various views of one of his own kinetic sculptures to emphasize

the gradations of light passing across the film frame rather than to document the material shape of the sculpture itself. The effect of this play

of light on the viewer takes on more importance than the object it refers to in the historical world. Similarly, Jean Mitry’s Pacific 231 (1944) is in part a

homage to Abel Gance’s La Roue and in part a poetic evocation of the power and speed of a steam locomotive as it gradually builds up speed and hurtles

toward its (unspecified) destination.

The editing stresses rhythm and form more than it details the actual workings of a locomotive. The documentary dimension to the poetic mode of representation stems largely from the degree to which modernist films rely on the historical world for their source material. Some avant-garde films such as Oscar Fischinger’s Composition in Blue (1935) use abstract patterns of form or color or animated figures and have minimal relation to a documentary tradition of representing the historical world rather than a world of the artist’s

imagining. Poetic documentaries, though, draw on the historical world for their raw material but transform this material in distinctive ways. Francis

Thompson’s N.Y., N.Y. (1957), for example, uses shots of New York City that provide evidence of how New York looked in the mid-1950s but gives

greater priority to how these shots can be selected and arranged to produce a poetic impression of the city as a mass of volume, color, and movement.Thompson’s

film continues the tradition of the city symphony film and affirms the poetic potential of documentary to see the historical world anew.

Origin

The poetic mode began in tandem with modernism as a way of representing reality in terms of a series of fragments, subjective impressions, incoherent

acts, and loose associations.These qualities were often attributed to the transformations of industrialization generally and the effects of World

War I in particular. The modernist event no longer seemed to make sense in traditional narrative, realist terms. Breaking up time and space into multiple

perspectives, denying coherence to personalities vulnerable to eruptions from the unconscious, and refusing to provide solutions to insurmountable

problems had the sense of an honesty about it even as it created works of art that were puzzling or ambiguous in their effect. Although some

films explored more classical conceptions of the poetic as a source of order, wholeness, and unity, this stress on fragmentation and ambiguity remains

a prominent feature in many poetic documentaries.

The historical footage, freeze frames, slow motion, tinted images, selective moments of color, occasional titles to

identify time and place, voices that recite diary entries, and haunting music build a tone and mood far more than they explain the war or describe

its course of action.

Examples

- Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali, 1928)

- L’Age d’or(Luis Buñuel, 1930)

- Scorpio Rising (Kenneth Anger, 1963)

- San Soleil (Chris Marker,1982)

- The Bridge(1928),

- Song of Ceylon (1934),

- Listen to Britain (1941),

- Night and Fog(1955),

- Koyaanisqatsi (1983).

We get to know none of the social actors in Joris Ivens’s Rain (1929), for example, but we do come to appreciate the lyric impression Ivens creates of a summer shower passing over Amsterdam.

Expository Documentary

|

Expository documentaries are prominent in today’s documentary culture, but began alongside the poetic documentary in the 1920s as an alternative to the often experimental films that were being produced. Expository documentary looks at an argument and then walks the audience through that argument, providing evidence to support the claims and reasoning. Similarly, Expository films can introduce an audience to a point of view, and explain to them the reason behind that point of view, as nature based expository films often do. These films are typically narrated, providing information about what you are seeing unfold on the screen. The film that is considered often as the first feature-length documentary, "Nanook of the North" (1922) falls into the category of an expository film. Nanook of the North used footage that the filmmaker Robert Flaherty had shot, and then a voice over recorded later to tell the story. This typically is used to create documentaries on historical subjects, as it allows archived footage and photographs to be shown and explained. Nature documentaries by companies such as the BBC, and National Geographic heavily rely on this style, as they can collect footage and then create a story with it after the fact.[5]

Participatory

Coming to bloom in the 60s and 70s shortly after Observational documentaries, participatory functions opposite to that idea. In this, the filmmaker interacts with and is a part of the story at times, often through interviewing subjects. This shift from the passive camera is described by Dr. Patricia Aufderheide as ‘somewhere in between an essay, reportage, and a well told tale’.[6] Participatory films not only tell a story to the audience, but they tell the filmmakers experience as well. This method rose to popularity alongside the invention of synced sound recording with video, and allowed for filmmakers to record direct interactions, eliminating the need for voice overs after the fact. The filmmaker’s role also shifts away from just recording to now directing, interviewing and guiding the story along.[7] The most famous example of this would be the famed The Thin Blue Line (1988), created by American filmmaker Errol Morris. In European film history, one of the first examples of participatory documentary is Chronique d’un été (1961). The french film translating to Chronicle of a Summer, was created with a British professor, French filmmaker and Canadian director. This team of creators open the film discussing their reasoning behind its creation, and then go on to to interview individuals about society and happiness. The film is recognized today for its innovative structure and unique approach to a documentary.[8]

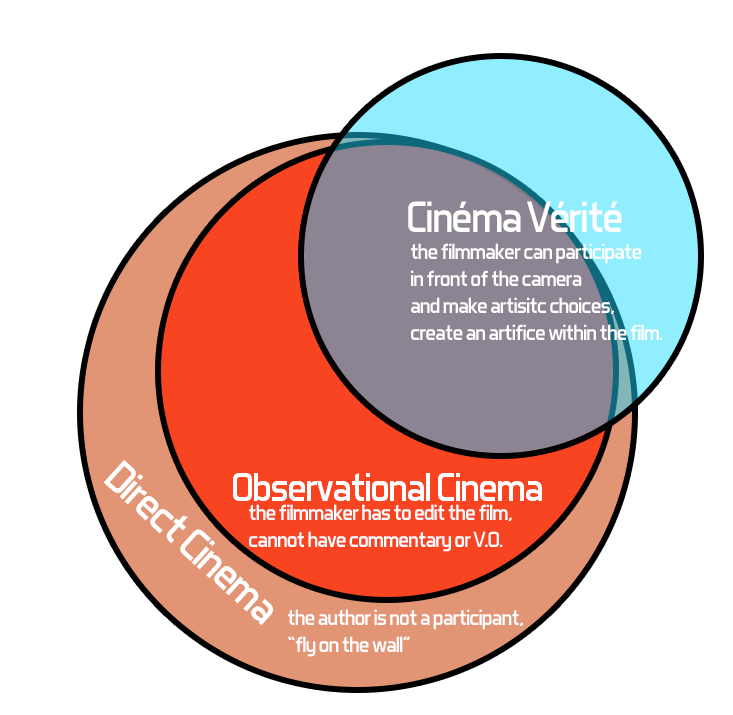

Observational (Cinéma Vérité)

Observational observational documentaries have their history in the Direct Cinema and cinéma vérité movements of the 1960s. As the name suggests, they involve no intervention, no commentary and no re-enactment, and in essence try to observe the action as it happens and unfolds. It emphasizes a direct engagement with the everyday life of subjects as observed by an unobtrusive camera. Although many films may have observational sequences in them, wholly observational films have a distinct aesthetic, often preferring to use small crews (often a single director) and handheld cameras. Classic observational films. include

general.

Examples

- High School (1968)

- Salesman (1969)

- Titicut Follies (Frederick Wiseman, 1967)

- Primary (1960)

- the Netsilik Eskimo series(1967–68)

- Soldier Girls (1980)

Origin

Examples

Creating a documentary

When starting with an idea about a documentary there are a lot of moving pieces that need to be addressed, and may different ways that directors and producers go about it. The New York Film Academy and the British Film Institute Academy have a lot of resources dedicated to laying down a foundation for new filmmakers to follow and ensure that they have covered the right grounds in this process. The subject and scope of documentaries can vary, which means that depending on the scale of the production, a lot more time and energy need to go into crafting these. Funding is an example of a step that we will be skipping over, as it has the most variation based on size of the production, and can be drastically different from film to film. Below are the outlined basic tasks that apply to creating any documentary, from a large budget production to a small student-led project.[9]

Pitch

Before writing a script and planning, it is essential that you have a short pitch that details exactly what you are setting out to create. The pitch will contain a few things:

- Title

- Logline - One or two sentence hook.

- Synopsis - A paragraph (or more) describing the project

- Locations - A few sentences about where the project will take place.

- Title

The pitch for large studio based projects usually is under 5 pages, while smaller projects will have a pitch of just a few sentences to ensure that all parties involved have an understanding of what could be created.[10]

Blueprint

At the Blueprint stage, you will be organizing and planning what material you will need to cover in order to tell your story to an inevitable audience. At this point, the blueprint is usually an outline that covers topics and themes, without going into technical details. The purpose of the Blueprint is to help breakdown the project into sections that allow for creative ‘wiggle room’ but still keep the fundamental story in place.[11]

Filming

In documentary work, the filming and principal production will take place before a script, with filmmakers working off of the Blueprint documents. In the field, these documents will have guides of what types of material to capture, and questions to ask, but no concrete assigned shots or scripted guide. This is because the story is usually told as it unfolds, and having a concrete script would not allow for that to happen. This typically varies depending on the filmmakers approach.

Script and Creation

Following principal production, the film’s script is then created before the story is crafted. Once data, research and footage is collected, the filmmaker’s job is to now utilize what they have and create the story the are trying to tell. This process occurs because the material that has been gathered can often change the initial plan of the film, and lead to the discovery of a more interesting story or details that were not initially known at the time of the pitch. A script will often be broken down into three categories for documentary: visuals, sound, narration/story. The visuals are where the shots of the story are laid out, and the audio next to it will be to arrange sound effects and music. The narration/story section will list either the script for a voice over or interview, or the purpose behind the shots listed in visuals. The director is now tasked with opening a door for the audience, into the information they have learned, and make sure their message is perceived in the development of the film.[12]

Section 2: Deliverable

Unit London | |

| location | SOHO, London |

|---|---|

Filming Process

We choose three galleries in London. We are going to do a documentary for each. Each documentary will have a different style.

Galleries Choosen

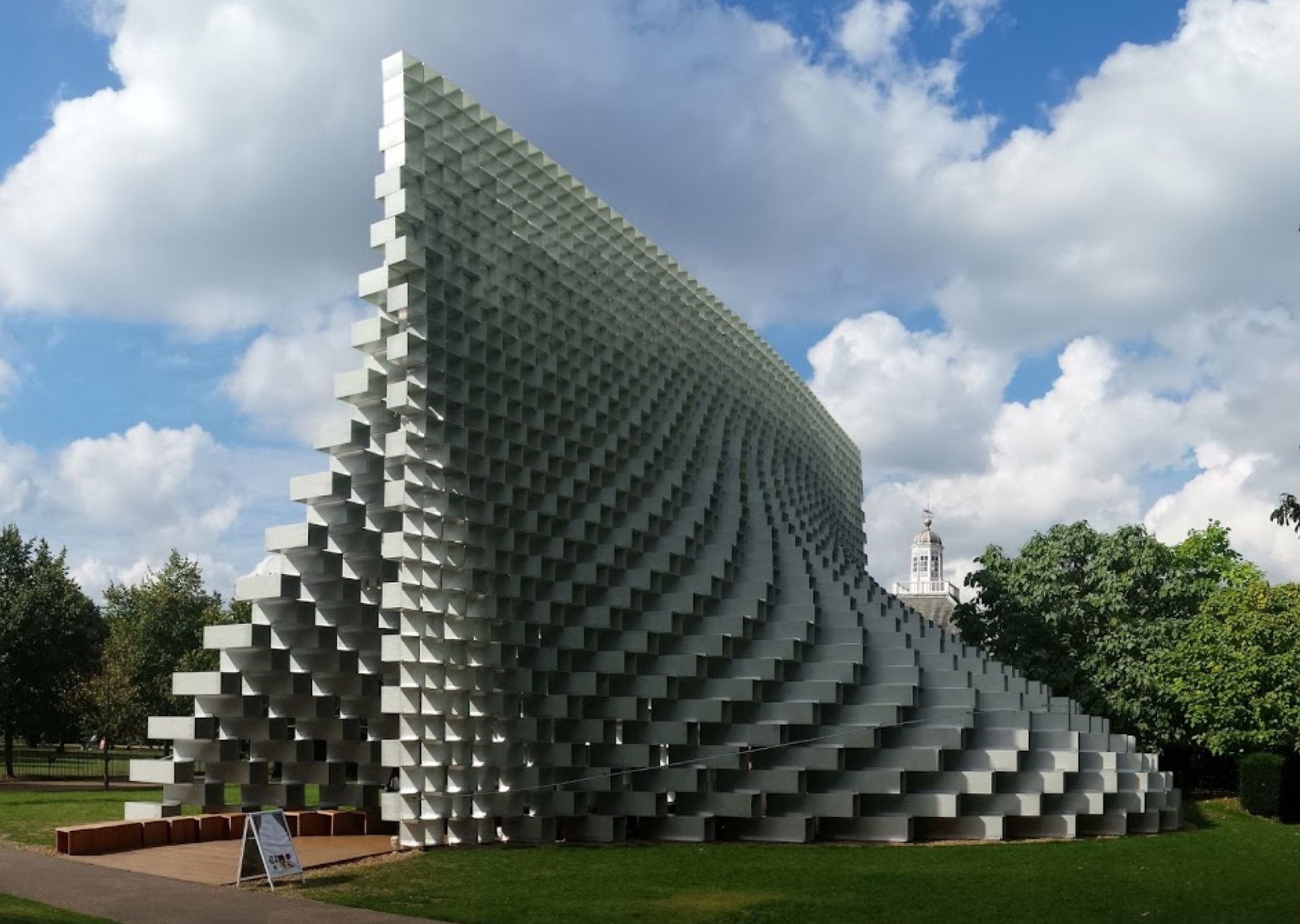

Serpentine Gallery & Pavilion

|

Gallery #1 | |

| location | Hyde Park, London |

|---|---|

Location -

History -

Purpose -

Current Displays -

Pavilion -

Transition

Unit London

Gallery #2 | |

| location | SOHO, London |

|---|---|

Location -

History -

Mission -

Current Exhibits -

Notable Exhibits -

Transition

White Cube

Locations -

History -

Purpose -

Current Displays -

Other Locations -

Transition -

Conclusion

Gallery

Conclusion

In this section, provide a summary or recap of your work, as well as potential areas of further inquiry (for yourself, future students, or other researchers).

Attribution of Work

For milestones completed collaboratively, add a section here detailing the division of labor and work completed as part of this milestone. All collaborators may link to this single milestone article instead of creating duplicate pages. This section is not necessary for milestones completed by a single individual.

External Links

Unit London

White Cube London

Serpentine Gallery Pavilion

BFI Reuben Library

Image Gallery

If appropriate, add an image gallery

References

- ↑ Aitken, I. (2006). Encyclopedia of the documentary film. New York: Routledge.

- ↑ (2014). "Chronology of Documentary History." California: UC Berkeley Media Resource Center.

- ↑ (2011). "Making History: Exhibition Guide, Section 1, Films: Defining Documentary" London, Tate Liverpool.

- ↑ Nichols, B. (2017). Introduction to documentary. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Pick, A., & Narraway, G. (Eds.). (2013). Screening Nature: Cinema beyond the Human. Berghahn Books. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qczx4

- ↑ Aufderheide, Patricia. "Public Intimacy: The Development of First-person Documentary." Afterimage, University of Minnesota. v25 n1

- ↑ Henderson, Julia. (2013) "Participatory and Reflexive Modes of Documentary Response and Theory." St. Edwards University. Vol. 4.

- ↑ (2008) "Chronicle of a Summer - 1961." London, British Film Institute.

- ↑ (2014) "How to Write a Documentary Script." NYC. New York Film Academy.

- ↑ (2011) "Documentary Process" London, BFI Reuben Library.

- ↑ Hugh Baddeley, W. (1996) "Technique of Documentary Film Production" London, Focal Press. p144.

- ↑ Ibid