Impact of the RAF on the Battle of Britain

From Londonhua WIKI

Impact of the RAF on World War II

Caption |

It is advised that you click Actions>Edit for this document, and copy the entire contents. Then, create a new page on this site using the title of your project as the page name. Past the copied contents from this template page into your newly created page. Then, rename the "Title of this Milestone" in the top-level heading and infobox above to the name of your project or something appropriate related to your milestone. Change the User "credit" name to link to your profile page. Upload an image of your own that captures the essence of this milestone, then replace the "ProjectPicture.jpg" above with the new image name. Replace "Your Project Page Picture Caption" above with your first and last name. Delete this whole paragraph beneath the Project Title and credit up til but not including the Table of Contents tag __TOC__.

Contents

- 1 Impact of the RAF on World War II

- 2 Abstract

- 3 Introduction

- 4 Section 1: Background

- 5 Section 2: Deliverable

- 6 Conclusion

- 7 References

- 8 Attribution of Work

- 9 External Links

- 10 Image Gallery

Abstract

The paragraph should give a three to five sentence abstract about your entire London HUA experience including 1) a summary of the aims of your project, 2) your prior experience with humanities and arts courses and disciplines, and 3) your major takeaways from the experience. This can and should be very similar to the paragraph you use to summarize this milestone on your Profile Page. It should contain your main Objective, so be sure to clearly state a one-sentence statement that summarizes your main objective for this milestone such as "a comparison of the text of Medieval English choral music to that of the Baroque" or it may be a question such as "to what extent did religion influence Christopher Wren's sense of design?"

Introduction

I suggest you save this section for last. Describe the essence of this project. Cover what the project is and who cares in the first two sentences. Then cover what others have done like it, how your project is different. Discuss the extent to which your strategy for completing this project was new to you, or an extension of previous HUA experiences.

As you continue to think about your project milestones, reread the "Goals" narrative on defining project milestones from the HU2900 syllabus. Remember: the idea is to have equip your milestone with a really solid background and then some sort of "thing that you do". You'll need to add in some narrative to describe why you did the "thing that you did", which you'd probably want to do anyway. You can make it easy for your advisors to give you a high grade by ensuring that your project milestone work reflects careful, considerate, and comprehensive thought and effort in terms of your background review, and insightful, cumulative, and methodical approaches toward the creative components of your project milestone deliverables.

Section 1: Background

Now you're on your own! Your milestone must include a thorough and detailed background section with detailed subsections; if additional articles are required to be referenced in this background section, create those as well and link to them (the creation of all pages is tracked by the wiki site and attributed to your username). Remember to use rich multimedia whenever possible. Consult the Help page as needed! Remember, if you don't see an article on this site that is an integral part of your project, create it! Your entire page-creating/page-editing history factors into your overall grade.

Aircraft Production Ramp up

...use as many subsections or main sections as you need to support the claims for why you did what you did for your Deliverable section...

Blenheim

Defiant

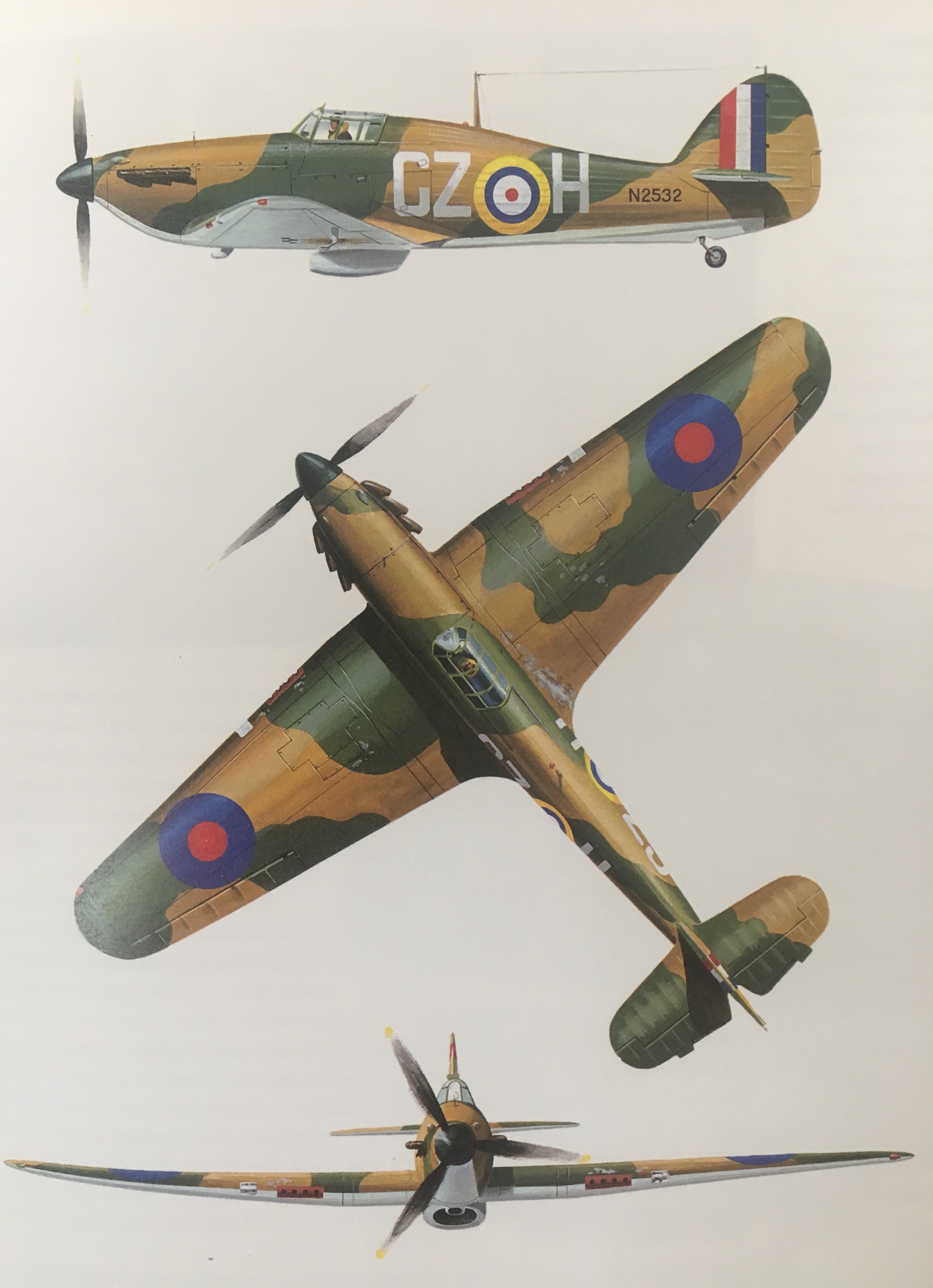

Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane was a single seat fighter/fighter-bomber. It was powered by one 1,280 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin XX V-12 piston engine. It had a maximum speed of 342 mph at 22,000 ft with a service ceiling of 36,500 ft. The range of the plane was 480 miles with internal tanks, but external tanks with a capacity of 90 gallons about doubled this range. The empty aircraft weighed in at 5,500 lbs, with a maximum take-off weight of 7,300 lbs. The plane had a wingspan of 40 ft, length of 32 ft 2 1/2 in, and a height of 13 ft 1 in. It was armed with 12 0.303-in forward-firing machine-guns, plus two 250 lb or one 500 lb bombs. The later versions of this aircraft replaced the 12 0.303-in machine guns with 4 20 mm cannons.[2]

Variants

Hurricane Mk I

Hurricane Mk IIC

Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire was a single seat day fighter. It was powered by a 1,030 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin II or III V-12 piston engine. It had a maximum speed of 355 mph at 19,000 ft with a service ceiling of 34,000 ft. It had a maximum range of 495 miles on its internal tanks. Empty it weighted in at 4,796 lbs with a maximum takeoff weight of 5,332 lbs. It had a wingspan of 36 ft 10 in, a length of 29 ft 11 in, and a height of 11 ft 5 in. It was initially armed with 8 0.303-in Browning machine guns, but later on in the war 20 mm Hispano cannons were introduced. There were several different wing designs that were used, one was the original 8 0.303-in machine guns, a second was 4 20 mm cannons, and the third was 4 0.303-in machine guns and 2 20 mm cannons.[3]

Variants

Spitfire Mk I

Spitfire Mk II

Spitfire Mk V

Fighter Command

The Fighter Command's Commander-in-Chief during the lead up to and during the Battle of Britain was Sir Hugh Dowding.[4] The role of Fighter Command was to repel any attack on Britain from the Luftwaffe, German Air Force. To best complete this mission Dowding had a plan to divide his resources across England. The No. 11 group which covered the south-east of the country was supplied with 12 Hurricane, 6 Spitfire, and 4 Blenheim squadrons. The No. 12 group which covers the East Anglia was supplied with 5 Hurricane, 5 Spitfire, 2 Blenheim, and 1 Defiant squadrons. The No. 13 group in the north was supplied with 3 Hurricane, 6 Spitfire, 1 Blenheim, and 1 Defiant squadrons. The No. 10 covering the west included 2 Hurricane, and 2 Spitfire squadrons. Many people felt that Dowding should have concentrated all of his best fighters in the No. 11 group as that was the most likely to encounter fighter opposition. Downding knew that the Battle of Britain would be a war of attrition and to keep a mix of fighter in less dangerous areas as a reserve would be important to the upcoming battle.[5] The Fighter Command had plenty of aircraft to go around with production ramping up, but pilots were much harder to replace. At the beginning of the Battle of Britain many squadrons were over-manned but as it dragged on training new pilots became a problem. As training took 6 months there were not enough pilots to have Fighter Command at full strength so the training courses were reduced to 4 weeks with the squadrons left to finish the pilot's training, sometimes with disastrous consequences.[6] Dowding was not the most liked leaders in the military and was eventually forced out of his position as the head of Fighter Command on November 17, 1940.[7] At the time no one recognized the importance of his work and how he saved Britain. Most importantly he set up a system of direction and control for his fighters to make the most out of his limited resources. Second, he pushed to limit the support of France in terms of aircraft that were essential to defending Britain in an air attack, which he didn't stop but helped reduce. Third, his careful placement and use of fighter resources to prevent being draw into a major battle and having his forces destroyed. His plan to keep fighters in reserve to reinforce the main No. 11 group was essential to this even though it gained much criticism.[8]

Fighter Command and Control System

Radar Stations

At the time Radar was known as Radio Direction Finding and the system that was in use by the British was simple but effective. The initial deployment was High Frequency radio Direction Finding (HF DF) to find the position of a friendly aircraft when out of sight of the controller. As the technology became refined Fighter Command became experimenting with radar controlled intercepts of unknown targets in 1936.[10] In 1937 the system in use was known as Pip Squeak, this system transmitted a coded DF signal for 14 seconds in every minute to allow the controllers to know the identity of each aircraft. To identify the other aircraft not using the Pip Squeak system they turned to physicist Robert Watson-Watt. This new technology was designated RDF which was rapidly developed, in only a few months the system was up and running being able to detect aircraft out to 58 miles. A string of these radar stations were built on the southern coast in 1936 and became fully operational in 1938.[11] This first chain of 21 stations was called Chain Home and utilized fixed antenna arrays. There was also another set of radar stations called the Chain Home Low stations, of which there were 30, that utilized a rotating antenna for a narrow search beam. These were not as effective as they had less range and could not give altitude information.[12] In addition to these radar advances, an improvement in plane identification was also being worked on. The new system was called IFF, Identification Friend or Foe. The IFF was a small transmitter that gave a distinctive radar blip to allow radar operators to differentiate between friend and foes.[13] When both friendly and enemy planes are spotted on radar that information is then sent to the Filter Room to be assessed.

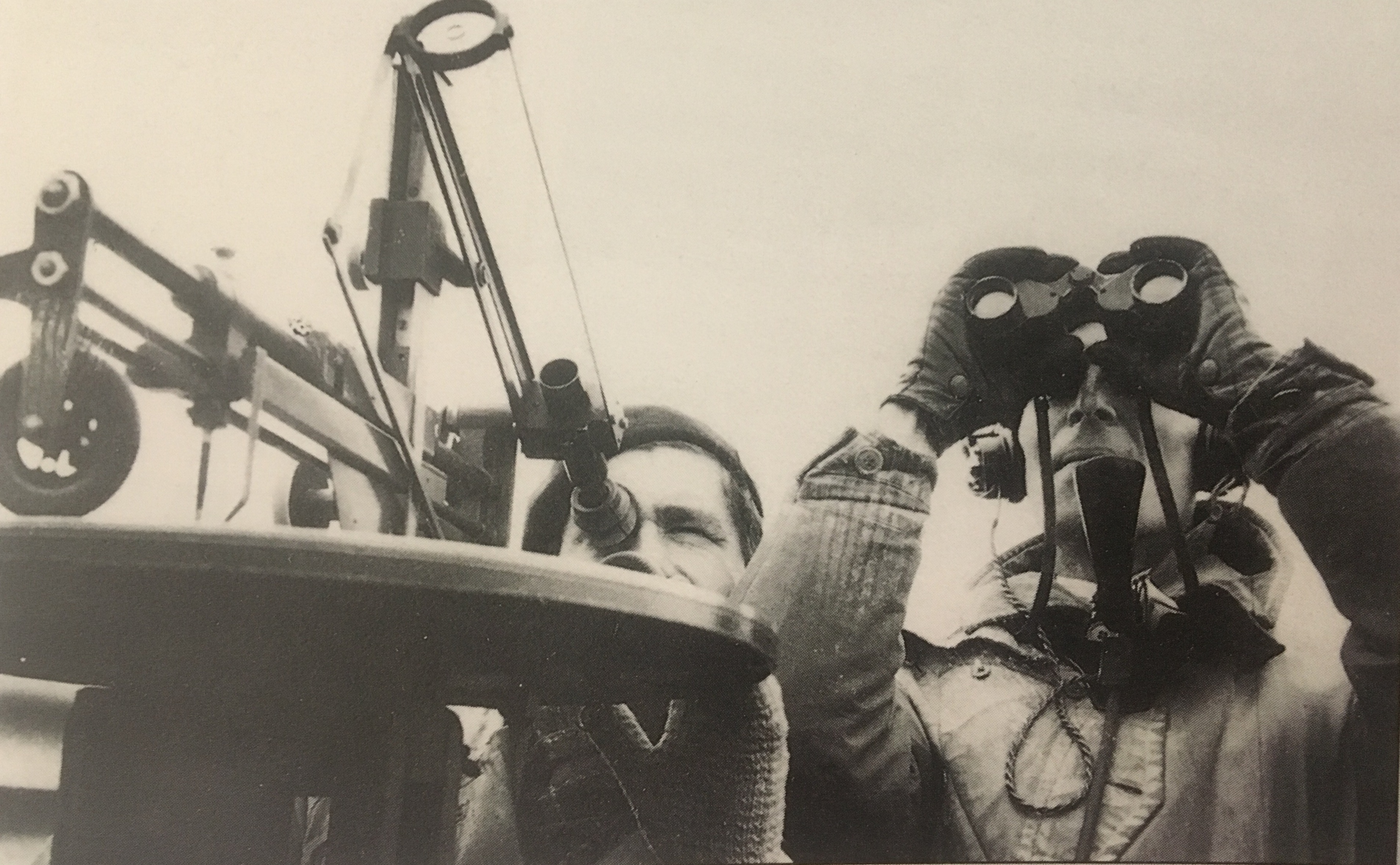

Observer Corps

The Observer Corps was a volunteer service meant to fill in the gaps of radar. Radar was amazing at looking out to sea but was blind to its back on land. This was the job of the Observer Corps, to track and report the movement of aircraft over land. Volunteers for the Observer Corps used binoculars, telescopes, and makeshift devices to determine the altitude and bearing of enemy aircraft. This technique was trialed in 1925 to outstanding success, after which the program rolled out rapidly to over 100 posts in that year. For the large roll out a map was divided up into 1.2 mile squares which then reported via telephone lines to their respective Group Headquarters. The full scale system across Britain was tested during the 1939 Air Exercises after which the posts were manned unbroken for 6 years until the end of the war.[15]

Fighter Command Operations Room and Filter Room

The Fighter Command and Operations Room was manned by the Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command, Commander-in-Chiefs of the Observer Corps and the Anti Aircraft Command, the liaison officers of Bomber and Coastal Commands, the liaison officer of the Admiralty, and the liaison officer for the Ministry of Home Security. The room housed the plotting table that displayed aircraft over all of the UK and the sea approaches. The Filter Room was located underneath the Fighter Command Operations Room. Its job was to receive all of the plots from the Radar Stations, compile them and cross reference the plots with the IFF plots. These cross referenced plots were then passed upstairs to the Fighter Command Operations Room.[16]

Group Operations Room

Sector Operations Room

Section 2: Deliverable

Interactive animation of RAF response for the defense of Britain

Conclusion

In this section, provide a summary or recap of your work, as well as potential areas of further inquiry (for yourself, future students, or other researchers).

References

Add a references section; consult the Help page for details about inserting citations in this page.

Attribution of Work

For milestones completed collaboratively, add a section here detailing the division of labor and work completed as part of this milestone. All collaborators may link to this single milestone article instead of creating duplicate pages. This section is not necessary for milestones completed by a single individual.

External Links

If appropriate, add an external links section

Image Gallery

If appropriate, add an image gallery

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 89.

- ↑ Gunston, B. (1982). British Fighters of World War II. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp 10.

- ↑ Gunston, B. (1982). British Fighters of World War II. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp 13.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 83.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 90.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 91.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 99.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 93-97.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 97.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 100.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 103-104.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 104.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 104.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 1112.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 109-111.

- ↑ Lake, J. (2000). The Battle of Britain. Silverdale Books. pp 105.