Modern Galleries in London: a Documentary

From Londonhua WIKI

Galleries in London

by Sofia Reyes and Jacob Dupuis

|

Documentary |

Contents

Abstract

Introduction

I suggest you save this section for last. Describe the essence of this project. Cover what the project is and who cares in the first two sentences. Then cover what others have done like it, how your project is different. Discuss the extent to which your strategy for completing this project was new to you, or an extension of previous HUA experiences.

Section 1: Background

History of Documentary

Since the early 1900s, filmmakers have been capturing and telling the stories of real people, places, and events along side fictional ones. The desire to learn or experience something new through film was growing. In 1926, John Grierson, a scottish filmmaker and expert, created the term Documentary, when reviewing the film Moana, by American filmmaker Robert Flaherty.[1] John Grierson was inspired by the works of Flaherty, and went on to create his own films in Scotland and Britain. He inevitably became in charge of the British Empire Marketing Board where he would oversee production of thousands of films produced in the United Kingdom. In 1929 he developed his own film Drifters, which would then be credited as the first British documentary, introducing the storytelling medium to the English.[2]

While documentary film is a popular informative method of filmmaking, often the difficulty and work put in to create these films is overlooked by the audience. With the rise of smaller, high quality cameras, and better editing capabilities, documentary is becoming even more widespread than ever and still is a popular field for award-winning productions to develop.

Types of Documentary

Every documentary has its own distinct voice. Like every speaking voice, every cinematic voice has a style or “grain” all its own that acts like a signature or fingerprint. It attests to the individuality of the filmmaker or director or, sometimes, to the determining power of a sponsor or controlling organization. Individual voices lend themselves to an auteur theory of cinema, while

shared voices lend themselves to a genre theory of cinema. Genre study

considers the qualities that characterize various groupings of filmmakers

and films. In documentary film and video, we can identify six modes of representation

that function something like sub-genres of the documentary

film genre itself: poetic, expository, participatory, observational, reflexive,

performative.

These six modes establish a loose framework of affiliation within which

individuals may work; they set up conventions that a given film may adopt;

and they provide specific expectations viewers anticipate having fulfilled.

Each mode possesses examples that we can identify as prototypes or mod-

99

Nichols, Intro to Documentary 8/9/01 10:19 AM Page 99

els: they seem to give exemplary expression to the most distinctive qualities

of that mode.They cannot be copied, but they can be emulated as other

filmmakers, in other voices, set out to represent aspects of the historical

world from their own distinct perspectives.[3]

To some extent, each mode of documentary representation arises in

part through a growing sense of dissatisfaction among filmmakers with a

previous mode. In this sense the modes do convey some sense of a documentary

history.The observational mode of representation arose, in part,

from the availability of mobile 16mm cameras and magnetic tape recorders

in the 1960s. Poetic documentary suddenly seemed too abstract and expository

documentary too didactic when it now proved possible to film everyday

events with minimal staging or intervention.

Poetic

'Subjective and Arttistic Expression'

Poetic Mode: emphasizes visual associations, tonal or rhythmic qualities,descriptive passages, and formal organization. This mode bears a close proximity to experimental, personal, or avant-garde filmmaking.

Poetic documentary can be compared with the Modernist Avant-garde. This type of documentary sacrifices the conventions of continuity editing and the sense of a very specific location in time and place that follows from it to explore associations and patterns that involve temporal rhythms and spatial juxtapositions. Social actors seldom take on the full-blooded form of characters with psychological complexity and a fixed view of the world. People more typically function on a par with other objects as raw material that filmmakers select and arrange into associations and patterns of their choosing.

|

The poetic mode is particularly adept at opening up the possibility of alternative forms of knowledge to the straightforward transfer of information, the prosecution of a particular argument or point of view, or the presentation of reasoned propositions about problems in need of solution.This mode stresses mood, tone, and affect much more than displays of knowledge or acts of persuasion. The rhetorical element remains underdeveloped.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Play of Light: Black, White, Grey (1930), for example, presents various views of one of his own kinetic sculptures to emphasize

the gradations of light passing across the film frame rather than to document the material shape of the sculpture itself. The effect of this play

of light on the viewer takes on more importance than the object it refers to in the historical world. Similarly, Jean Mitry’s Pacific 231 (1944) is in part a

homage to Abel Gance’s La Roue and in part a poetic evocation of the power and speed of a steam locomotive as it gradually builds up speed and hurtles

toward its (unspecified) destination.

The editing stresses rhythm and form more than it details the actual workings of a locomotive. The documentary dimension to the poetic mode of representation stems largely from the degree to which modernist films rely on the historical world for their source material. Some avant-garde films such as Oscar Fischinger’s Composition in Blue (1935) use abstract patterns of form or color or animated figures and have minimal relation to a documentary tradition of representing the historical world rather than a world of the artist’s

imagining. Poetic documentaries, though, draw on the historical world for their raw material but transform this material in distinctive ways. Francis

Thompson’s N.Y., N.Y. (1957), for example, uses shots of New York City that provide evidence of how New York looked in the mid-1950s but gives

greater priority to how these shots can be selected and arranged to produce a poetic impression of the city as a mass of volume, color, and movement.Thompson’s

film continues the tradition of the city symphony film and affirms the poetic potential of documentary to see the historical world anew.

Origin

The poetic mode began in tandem with modernism as a way of representing reality in terms of a series of fragments, subjective impressions, incoherent

acts, and loose associations.These qualities were often attributed to the transformations of industrialization generally and the effects of World

War I in particular. The modernist event no longer seemed to make sense in traditional narrative, realist terms. Breaking up time and space into multiple

perspectives, denying coherence to personalities vulnerable to eruptions from the unconscious, and refusing to provide solutions to insurmountable

problems had the sense of an honesty about it even as it created works of art that were puzzling or ambiguous in their effect. Although some

films explored more classical conceptions of the poetic as a source of order, wholeness, and unity, this stress on fragmentation and ambiguity remains

a prominent feature in many poetic documentaries.

The historical footage, freeze frames, slow motion, tinted images, selective moments of color, occasional titles to

identify time and place, voices that recite diary entries, and haunting music build a tone and mood far more than they explain the war or describe

its course of action.

Examples

- Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali, 1928)

- L’Age d’or(Luis Buñuel, 1930)

- Scorpio Rising (Kenneth Anger, 1963)

- San Soleil (Chris Marker,1982)

- The Bridge(1928),

- Song of Ceylon (1934),

- Listen to Britain (1941),

- Night and Fog(1955),

- Koyaanisqatsi (1983).

We get to know none of the social actors in Joris Ivens’s Rain (1929), for example, but we do come to appreciate the lyric impression Ivens creates of a summer shower passing over Amsterdam.

Expository

Describing a scenario / ‘voice of god’

Origin

goes back to the 1920s but remains highly influential

today

Ken Burns, Nature Movies

Participatory

Filmmaker is included, and guides through the story.

Origin

Examples

Observational (Cinéma vérité)

general.

Observational Mode: emphasizes a direct engagement with the everyday

life of subjects as observed by an unobtrusive camera. Examples: High

School (1968), Salesman (1969), Primary (1960), the Netsilik Eskimo series

(1967–68), Soldier Girls (1980).

Participatory Mode: emphasizes the interaction between filmmaker and

subject. Filming takes place by means of interviews or other forms of even

more direct involvement. Often coupled with archival footage to examine

historical issues. Examples: Chronicle of a Summer (1960), Solovky Power

(1988), Shoah (1985), The Sorrow and the Pity (1970), Kurt and Courtney

(1998)

Origin

Examples

Reflexive

Filmmaker does not use outside subjects, only explains how the film was created as it unfolds.

Writing a documentary

Brainstorming a concept

Creating a story

Planning a documentary

Production

Developing a concept into a film

Section 2: Deliverable

Selecting Galleries

In this section, provide your contribution, creative element, assessment, or observation with regard to your background research. This could be a new derivative work based on previous research, or some parallel to other events. In this section, describe the relationship between your background review and your deliverable; make the connection between the two clear.

Filming Process

...use as many subsections or main sections as you need to support the claims for why what you did related to your Background section...

Final Video Outline

Introduction

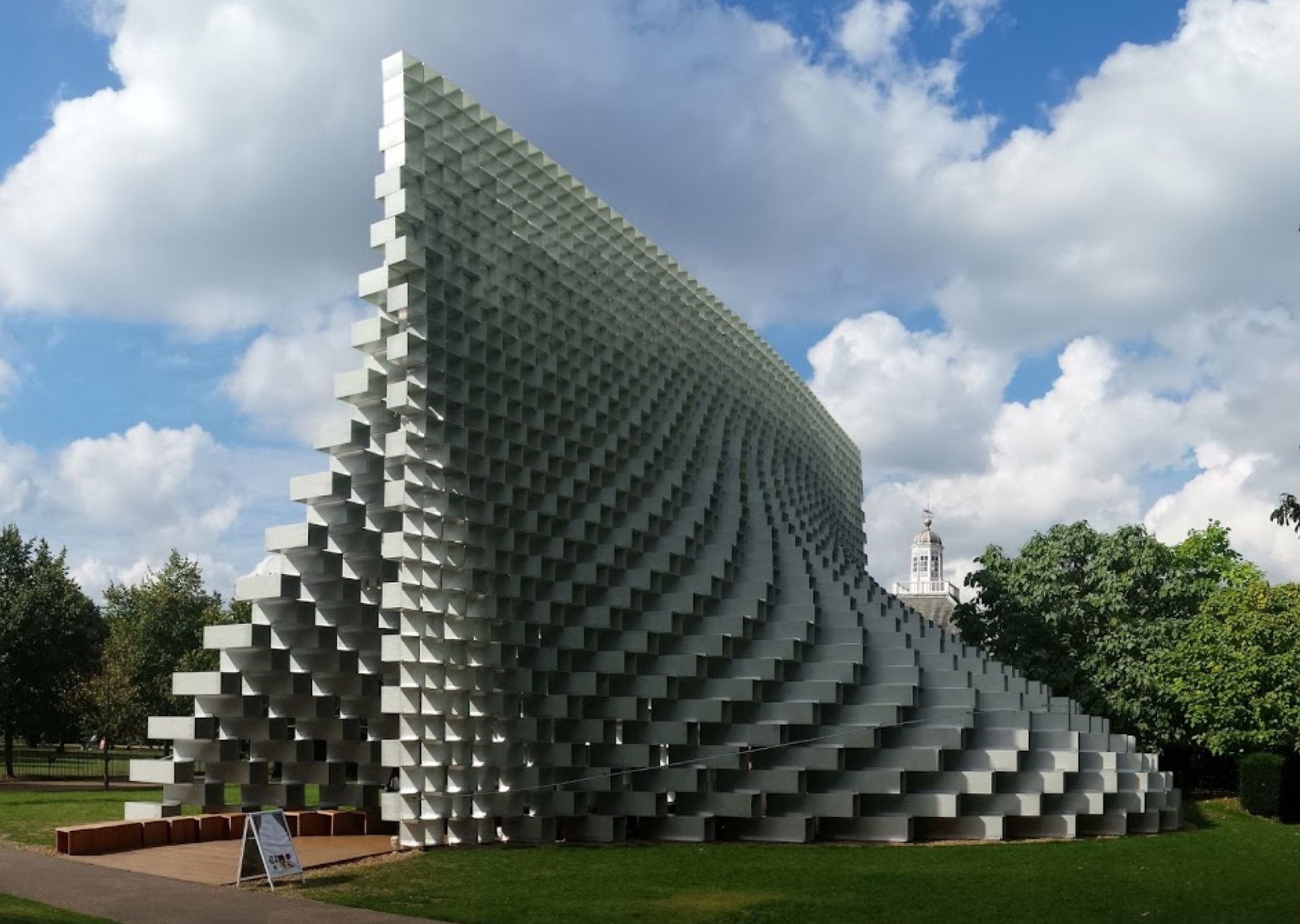

Serpentine Gallery & Pavilion

Location -

History -

Purpose -

Current Displays -

Pavilion -

Transition

Unit London

Location -

History -

Mission -

Current Exhibits -

Notable Exhibits -

Transition

White Cube

Locations -

History -

Purpose -

Current Displays -

Other Locations -

Transition -

Conclusion

Gallery

Conclusion

In this section, provide a summary or recap of your work, as well as potential areas of further inquiry (for yourself, future students, or other researchers).

References

Add a references section; consult the Help page for details about inserting citations in this page.

Attribution of Work

For milestones completed collaboratively, add a section here detailing the division of labor and work completed as part of this milestone. All collaborators may link to this single milestone article instead of creating duplicate pages. This section is not necessary for milestones completed by a single individual.

External Links

If appropriate, add an external links section

Image Gallery

If appropriate, add an image gallery